By John Seigenthaler

When first invited to contribute this reminiscence of the troubling, tragic time when James Meredith first crossed the threshold at Ole Miss, it struck me that perhaps this story has outlived its relevance.

So much has changed in fifty years. So much is different. Beyond the names on the buildings, so little is recognizable. So much has improved.

And, after all, there are volumes of histories and biographies, stacks of articles, and hours of documentaries vividly recounting the violent confrontation between the federal government and the state of Mississippi. There are tape recordings memorializing the words exchanged in three terse telephone conversations between President John F. Kennedy and Governor Ross Barnett.

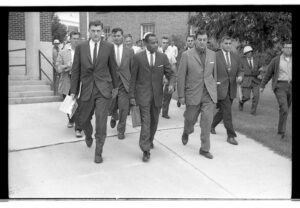

And, after all, there are photographs capturing the anger on the countenances of members of the mob as Meredith moved among them, protected by James McShane, the chief U.S. marshal, acting on the orders of the president.

And, after all, on each decade of the anniversary, and sometimes annually, Ole Miss has gone out of her way to make certain that her painful mea culpa again resounds: “through my fault.”

And, after all, black enrollment this year climbs to more than 16 percent. And, the 2012 Ole Miss homecoming queen is an African American. And, when Rebel varsity athletes perform at Hemmingway-Vaught, or in the Tad Pad, students pack the arenas to cheer black athletes, men and women who are admired by alums and students alike.

And, after all, Meredith’s son has long since graduated with highest honors from the university’s school of business administration.

And finally, after all the rest, I was not here at the time. I did not set foot on campus as Ole Miss suffered the self-inflicted wound that bleeds profusely each decade as her sons and daughters once more pick the scab from the sore that gradually, but surely–like so much of the South– is healing.

And yet, I, like every caring American citizen, in a sense was here. Our minds and hearts, if not our footprints, were in step with Meredith; with the effort to put an end to the vicious, vulgar, racism that infected this place–but, also, too much of the nation. We were shocked and sickened by it all, if from the distance.

But, even so, should we not finally, after five decades, put behind us what Will Campbell’s song calls “Mississippi Madness?”

Barack Obama resides in the White House now, his presence made possible by what happened here with Meredith and across the South with other heroes and martyrs of the movement.

And yet, on the night of Obama’s reelection, amidst partisan celebration and sadness, there was raised once more, here at Ole Miss, and elsewhere, cries of the racist rhetoric, echoing from the night of riot. Thus, we dare not forget the madness. There is value in remembering; in reliving it all.

* * *

One September morning, a half-century ago, a mirror image of the Ole Miss campus would have reflected a picture-perfect academic enclave of the time–with 4,770 recently enrolled students celebrating their Rebels’ first victory of another undefeated football season.

And then, another morning, just a week later, that serene academic scene was transformed by a murderous mob, bent on violence, into a devastated war zone. Two men had been shot dead the night before. Dozens of others, most of them federal police officers there to keep peace, had been shot, stoned, endangered, some hospitalized.

The Lyceum lawn and walkway were strewn with random debris–stones, bricks, pieces of pipe and shattered glass from bottles that had been Molotov cocktails. The driveway encompassing the Grove was pockmarked by abandoned, burned-out automobiles. And, there still was the lingering, acrid odor of tear gas, mingled with the pungent smell of gun smoke, wafting from the Circle to Bondurant to Baxter Hall.

By this time, the Rebels, playing in Jackson, had won their second game of the season–but the riot had left a sense of depression on campus, so that the occasional celebrative, morning-after rebel yells rang hollow–from angst, or guilt, or anger.

If there was any spirit of celebration in the wake of the mob action, it was tinctured by the reality that criminality on this revered (and soon to be reviled) campus, had snuffed out human life, wounded peace officers, vandalized valued property, and decimated the reputation of the University of Mississippi–the proud Ole Miss.

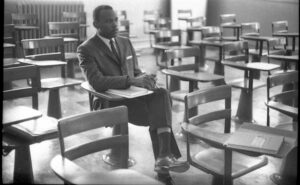

And worse, there was the knowledge that James Howard Meredith, a Negro, had spent the night at Baxter; that he was now relaxing in the Lyceum.

“Meredith.” The word spat from the lips of many students and most Mississippians as an obscenity. None of them knew him–but they knew enough about him to despise him.

He was the black man (although that’s not the way most who hated him referred to him) who had dared despoil the hallowed 114-year tradition of an all-white university by seeking admission. The press had reported that he had served almost a decade in the U.S. Air Force, a staff sergeant when discharged. He had been a student at historically black Jackson State, and now wanted to graduate with the Ole Miss class of 1963.

And, they knew he had consulted with Medgar Evers, the hated state leader of the NAACP who had helped arrange for that organization’s lawyers to represent him.

So, the saga of how segregation ended at Ole Miss is a story filled with passion and pathos and pain–and irony.

An irony: In the minds of a majority of Mississippians, what Meredith intended to do had never been done before. And would not be done now, said Governor Ross Barnett, the state legislature and the State Sovereignty Commission. And, so said members of the Ku Klux Klan who rushed in from across the region to meld with the student rioters and wage war against their federal government.

Except, it had been done before. A black student had attended Ole Miss. As controversy swirled around the legal fight over Meredith’s application for admission, a man named Harry Murphy, Jr., a native of Atlanta, now living in New York, publicly stated that in 1945, while in the Navy, he had been sent to Ole Miss as part of a V-12 military education program. He had pursued a liberal arts course of study, never disclosing his ethnicity to anyone. The Navy had mistakenly listed his race as “Caucasian.” He never sought to correct that record. He had attended football games and dances, and had been accepted by unsuspecting fellow students and faculty. Murphy’s surprising disclosure, easily and immediately confirmed, did nothing to slake the hostile opposition to Meredith’s enrollment at the university. It may have intensified it.

An irony: Major General Edwin Walker, the army officer who commanded the federal troops President Eisenhower sent to Little Rock to enforce a court desegregation order at Central High School, had resigned from the Army during the Kennedy administration–and now was making racist trouble at Ole Miss. A few nights before the violence broke out, General Walker delivered a radio speech in which he condemned President Kennedy and the “anti-Christ Supreme Court” that had ordered Meredith admitted to Ole Miss. Walker called on Mississippians to join in support for Governor Barnett and in forceful opposition to President Kennedy.

“Last time (at Little Rock) I was on the wrong side,” Walker declared. “…This time I am on the right side. I will be there.”

And he was. As tension and anger infected the mob on the Lyceum, Walker, standing near the Confederate Memorial on the Circle, launched into a harangue, urging the mob to accelerate the assault on the marshals. An Episcopal priest, the Rev. Duncan Gray, wearing his clerical collar, spoke out, pleading with Walker to calm his rhetoric and, instead, to try to defuse the violence. The general turned on the minister, demanding his identity.

“I am Duncan Gray, a local Episcopal minister,” said the priest.

“Well, you are the kind of minister that makes me ashamed I am an Episcopalian,” retorted Walker. He continued his diatribe as those listening began to strike out at Reverend Gray.

And so, the erupting riot built in intensity. The marshals, under orders not to fire their weapons into the crowd, began to fall under the barrage of gunfire and missiles aimed at them. Tear gas only briefly slowed the assault. At Walker’s urging, it worsened. The General, arrested the next day by marshals, was charged with inciting insurrection. The charges later were dropped.

Perhaps the most compelling irony that is part of the Ole Miss desegregation drama, has to do with the life-after-graduation of James Meredith. A man of intelligence and courage, Meredith was an iconoclast. During the crisis, I engaged in two personal telephone calls with my old friend, Jim McShane, the chief U.S. marshal, who was at Meredith’s side throughout the days of danger.

“He’s fearless and ballsy,” McShane said of his student ward. “But he’s walking to some other drumbeat than mine. He talks to himself more than he does to me.” And, he added, “My guess is we’ll hear from him again when this is all over. He may even run for class president.”

McShane, always a man of good humor, was prophetic. Meredith was determined to be heard from. Much later, Meredith would write of himself: “I befuddle people…They have a hard time figuring me out. A lot of folks think I’m a real odd bird.”

He knew himself. In 1966, he initiated what he called “The March Against Fear” from Memphis through Mississippi to Jackson, to promote the cause of voting rights. He was shot down by a sniper on the second day of the trek. He recovered from the wound and rejoined the march a few days later. And yet, he was always offended when journalists later described him as a participant in the civil rights movement. He considered it an insult, he said. And, he demeaned Martin Luther King’s concept of non-violence.

On leaving Ole Miss (his major was political science) Meredith earned a law degree at Columbia University in New York. He never took the bar and never sought to practice. In New York, he surprised liberals who had felt an emotional bond with him, by declaring as a candidate against the veteran Harlem congressman, Adam Clayton Powell. Meredith withdrew from that race before Election Day, stating that his reasons for challenging Powell “may never be known.”

The following year, another surprise: he endorsed the losing campaign of former Governor Ross Barnett. Still later, he ran as a Republican candidate against Mississippi’s ensconced senator, James Eastland — a campaign as ill conceived as the brief bid against Powell. Still later, he announced his support for David Duke, the Ku Klux Klan candidate for Governor. In between his several rudderless political journeys, he joined the staff of U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms, the constant critic of Martin Luther King and the movement. Meredith was right. He did befuddle people.

Meredith’s diverse personal and political post-graduate activity may have rendered him irrelevant a half-century later–but the riotous events that despoiled, then changed the character of the campus forever, and ultimately for the better, remain relevant for yet another generation.

On the day the Meredith statuary was unveiled, those who spoke (he did not) reflected with passion and power on the meaning of his tenure at Ole Miss. Chancellor Robert Khayat predicted that the monument would remind later generations of the undaunted courage of Meredith and other fearless leaders who risked their lives to change a racist society. Congressman John Lewis, who suffered beatings, abuse and prison because of his non-violent leadership of the movement, defined the statuary as “a monument to peace over violence,” and “love over hatred.” And, former Mississippi Governor William Winter said, “The memorial tells us, not where we have been, but where we are going.”

He was right. There still is a way to go.

–John Seigenthaler Sr. served for 43 years as an award-winning journalist for The Tennessean. In 1982, Seigenthaler became founding editorial director of USA TODAY and served in that position for a decade, retiring from both the Nashville and national newspapers in 1991. During the 1960s, Seigenthaler served as administrative assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. His work in the field of civil rights led to his service as chief negotiator with the governor of Alabama during the Freedom Rides

This article was originally published in the Meek School of Journalism and New Media Alumni Magazine and appears here with permission.

Recent Comments