This is the second segment in a two-part series on the evolution of the term “Ole Miss.” The piece is written by Dr. Albert Earl Elmore, a noted scholar who holds degrees from Millsaps College and Ole Miss Law School with a Ph.D in English Literature from Vanderbilt.

The History of the Name “Ole Miss”

The controversy about “Ole Miss” as a name for the University of Mississippi was conceived in innocent ignorance and perpetuated by the misinformation of the Internet.

Let us begin with the Internet misinformation that appears in the endlessly consulted Wikipedia entry for the name Ole Miss: “The student yearbook was published for the first time in 1897. A contest was held to solicit suggestions for a yearbook title from the student body. Elma Meek, a student, submitted the winning entry of ‘Ole Miss.’ Meek’s source for the term in unknown. Some historians theorize she made a diminutive of ‘ole Mississippi’ or derived the term from ‘ol missus,’ an African-American term for a plantation ‘old mistress.'”

An article published on May 13, 1939, in the Ole Miss student newspaper, the Mississippian, demonstrates that much of this is pure mythology. The unnamed student author of that article got in touch with the living members of the original board of editors, including the members of the committee that was established to find a name for the yearbook. Not one of them mentioned a contest to find the name. Instead, the committee asked people in the community for suggestions.

A poetess named Mrs. Coppleman of Okolona suggested the name “Cotton Boll.” A committee member named J.A. Mills got in touch with a local family and “asked the Misses Meek of Oxford ” for their ideas. One of the Meek sisters, Elma, suggested “Ole Miss,” and Wills took her suggestion back to the committee. “The name appealed to us at once,” said Mrs. Maud Morrow Brown, a committee member who was still living in Oxford in 1939. because her husband, Calvin was a member of the University faculty, “and it was adopted.”

Maurice Fulton, who served as one of the student business managers, suffered a failure of memory by attributing the suggestion to the wrong person but agreed with Mrs. Brown that “those of the board who were present at the meeting which was to make the selection voted heartily for (the ‘Ole Miss’) selection.”

There is not a shred of evidence that Elma meek was a student at the University of Mississippi when she offered the suggestion. She apparently had attended during the 1894-95 year but then dropped out. Her name appears nowhere in the 1896-97 yearbook. There is not a shred of evidence that she herself ever appeared before the selection committee. There is not a shred of evidence that J.A. Mills , who solicited her suggestion and relayed it to the committee, offered any arguments on behalf of Elma’s suggestion, either hers or his own. The name “Ole Miss” was offered, it met with immediate and unanimous favor, and it was “heartily” approved. Those are the known facts.

The 1939 article went on to interview Mrs. meek herself. This is where the plot not only thickened, but curdled. “Miss Meek, who today resides in Oxford, took the name from the Ante-Bellum ‘Darky,’ who knew the wife of his owner by no other title than ‘Ole Miss,’ and of how she suggested it because she thought it connoted the tribute due the womanhood of the old South.”

However, as soon as the unnamed student reporter quoted Miss Meek herself, it became immediately clear that the originator of of the “Ole Miss” name was referring, not to antebellum plantations but to the plantations of her own day.

In her day, sharecropping was the norm. “I had often hear old ‘darkies’ on Southern plantations,” she was quoted as saying “address the lady in the ‘big house’ as ‘Ole Miss.’ The name appealed to me, so I suggested it to the committee and they adopted it.”

Elma Meek never lived during slavery. There is no way she could have heard slaves talking. She was born somewhere around 1878, well after the Civil War had ended some 250 years of American slavery.

Even if Miss Meek knew the name had previously been used for the wife of the Ole Massa on antebellum plantations, there is not a shred of evidence that she intended to invoke that association. Even if she did, there is not a shred of evidence that she conveyed any such idea to J.A. Willis or that he, in turn, conveyed it to the committee, which so immediately and heartily approved it. Even in the most unlikely event that all these things did happen, where is the evidence that this information was passed down, year to year, from class to class, generation to generation.

On the contrary, the immediate approval by the selection committee suggests that there was no need for any explanation. The main competition was “Cotton Boll.” How in the world would “Cotton Boll” have separated the yearbook of the University of Mississippi from the yearbooks of the University of Alabama or the University of Georgia? Every sound and suggestion of “Ole Miss” ties the name to the oldest university in the state of Mississippi while clearly distinguishing it from all of its rivals.

The evolution of the name from yearbook title only to university title as well supports the idea that students naturally associated the name with the state of Mississippi and its flagship university.

For 12 years, from 1897 through 1908, every yearbook called itself “Ole Miss” without ever using that term in reference to the university as a whole. year after year, the football scores appeared in the yearbook. In every case, the football team was called “Mississippi,” never “Ole Miss.”

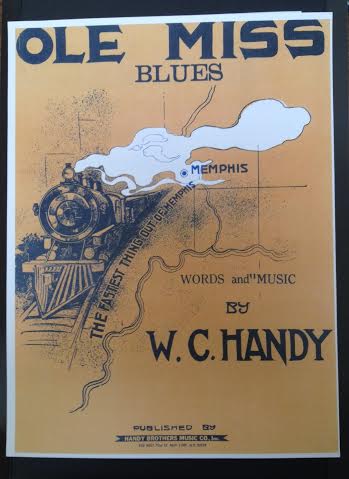

In 1909 a dramatic change occurred. On the first full page of the yearbook for that year appeared a drawing of a train with the name “OLE MISS” written in white inside a circle on the train’s black-metal face. My earlier essay on W.C. Handy (here) documents that he would soon write about a train called “The Ole Miss” that ran from memphis to New Orleans, transversing the entire length of Mississippi . It is the state of Mississippi that is clearly invoked in the name of that train.

In the 1909 yearbook, for the first time ever, the name Ole Miss was applied to the university as a whole in the “ATHLETICS” section. That section opened with “FOOTBALL Yells” and “College Songs.” The second of the two football yells referred to Ole Miss in its opening lines: “Hurrah, ‘Ole Miss,’ we’ll raise a song to thee./ Hurrah, ‘Ole Miss’ we’ll ever loyal be;/ We’ll put aside all care today and join the Jubilee,/ While we shout for Mississippi.”

Of the four College Songs, one referred to Ole Miss in its chorus: “here’s to ‘Ole Miss,’ the school we love,/ Here’s to the Red and Blue;/ Here’s to the men who wear the ‘M’/ Here’s to our roster true.”

Yet another reference of the same kind appears in the 1909 yearbook. A 1902 graduate named Marvin Holloman Brown wrote an essay in which he pretended to re-live, but admitted at the end he was only imagining, a game between Mississippi and Vanderbilt : “What a victory we felt was ours can be appreciated only by one of Ole Miss’ devotees!”

The next step in the evolution of the name appeared in the 1912 yearbook. There, for the first time, the name appeared without quotation marks and in a context other than athletics. Under the photograph of a graduating senior, appeared the caption: “it will probably be long in the future before Ole Miss will have another John Kyle.” the senior class history used the name free of quotation marks three different times: 1. “Everybody who has ever heard of Ole Miss knows our history from Alpha to Izzard.” 2. “About this time we came to Ole Miss — said school is grateful — and took these classic old shades by storm.” 3. “Long live Ole Miss, and may her days of prosperity be numberless as the sands of the seashore.”

The final name in the evolution of the name appeared in the 1915 yearbook. There, for the first time, the name appeared on a sports uniform. A picture of a basketball player shows Ole Miss written across the front of his jersey. In a cartoon of a student reading in his room. an Ole Miss pennant shows the female players holding a huge pennant bearing the name Ole Miss, and a baseball player is pictured with Ole Miss sewn on his jersey.

Nor was the name restricted to athletic teams. In these yearbooks, the school orchestra was photographed above its title, “The Ole Miss Orchestra.”

The current administration has suggested that the name “Ole Miss” should be restricted only to “appropriate” uses, although that initiative seems to have been wisely abandoned. There is nothing inappropriate about using this venerable old name to refer to the University of Mississippi in all its functions, just as our neighboring institution, Louisiana State University, refers to itself in all its functions as LSU.

Both schools are using traditional shortenings of their names in a way that is not only appropriate but highly appealing to an overwhelming majority of their graduates and supporters.

The winner of six grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, he is the author of essays on Faulkner and Fitzgerald as well as the 2009 book, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: Echoes of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer.

Dr. Elmore, after years of research, has unearthed both the words and music of the classic, but long-forgotten song “The Ole Miss Blues.” Dr. Elmore has written two essays on the topic; the first on the song itself, a poetic and colorful work by the composer W.C. Hardy, who was also a scholarly professor of music as well as a famed performer. Click here to review this post.

Dr. Elmore’s second essay traces the history of the phrase “Ole Miss” arguing persuasively through historical references that the term “Ole Miss” referred not only to the state of Mississippi generally, but specifically to a Memphis-to-New Orleans train that may even have stopped at the Old Oxford Depot. (recently restored as a Conference Center) where it could have dropped off many returning Ole Miss students.

A copy of the sheet music is attached with his essay. Dr. Elmore is currently working with local Blues scholars to combine the words with the music to create a true “Ole Miss Blues” song to perform at athletic and other campus events.

Recent Comments