This story is about Kåre Melhus, a reporter during the Balkan conflict in the early ’90s, and is featured in The Meek School Magazine. The magazine is a collaborative effort of journalism and Integrated Marketing Communications students with the faculty of Meek School of Journalism and New Media. Every week, for the next few weeks, HottyToddy.com will feature an article from Meek Magazine, Issue 4 (2016-2017).

The conflict between radical Islam and the West has been fought for centuries in the Balkans, and everywhere there are memorials to the dead from one conflict or another.

I realized the enduring nature of the conflict several years ago at a reception on the top floor of a bank building in Belgrade, Serbia.

My host and I looked down on Belgrade Fortress, situated where the Danube and Sava rivers meet.

“That fort has changed hands dozens of times between the Hapsburgs and the Ottomans,” he said.

The next day we were to hear a speech by Boris Tadić, the president of Serbia. He would tell us that his administration was committed to bringing to justice those who had committed war crimes during the recent Balkan conflict.

***

Last October an associated (cq) professor at NLA University College, the second-largest private higher education institution in Norway, and I were in the Balkans to attempt to move the Kosovo Institute of Journalism and Communication to one of the public institutions of higher learning in that newly formed nation.

If the program is transferred, we are hopeful that Meek School faculty will teach journalism and integrated marketing communications in Kosovo in the near future.

Kåre Melhus covered the Balkan conflict. He is a graduate of Trinity International University in Deerfield, Illinois, and was awarded a graduate degree in journalism by the University of Missouri.

His school offers a master’s degree in global journalism and has been involved in establishing graduate journalism programs at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia and the Kosovo Institute of Journalism and Communications in Pristina, Kosovo.

During our time in the Balkans, we spent a day in Sarajevo where Melhus briefly had covered the siege of that city by Serbian forces.

Tito’s Yugoslavia had gradually declined, and the disintegration continued after his death. In October 1991, Bosnia-Herzegovina declared independence. In reaction, Slobodan Milošević, a Serbian, and Franjo Tuđman, a Croatian, agreed to take portions of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Bosnian Serbs established the Republic of Srpska east of Sarajevo.

By April 1992, Serbian paramilitaries and members of the Yugoslav Army had laid siege to Sarajevo, and more than three years of ethnic cleansing ensued. Serbs in the hills surrounding Sarajevo lobbed mortars into the city every day.

Two bombardments by the Army of the Republic of Srpska targeted civilians during the siege of Sarajevo. They occurred at the marketplace in the historic center of the city. The first was Feb. 5, 1994, killing 68 and wounding 144. The second was on Aug. 28, 1995, when mortars killed 43 and wounded 75 Bosnians. NATO responded with airstrikes in September. The damage was so severe that Balkan leaders accepted President Bill Clinton’s invitation to a peace conference in Dayton, Ohio.

At that conference Richard Holbrooke convened the delegates in a hangar in Dayton. The discussions did not seem to be heading toward peace, and Holbrooke told the participants that they had a deadline, and the discussion would end at that deadline unless they reached an agreement.

* * *

“I did a lot of reporting from Oslo based on wire stories,” Melhus said, “but I was sent to Sarajevo then to find out how people on the ground would react to a peace accord. I flew commercially into Zagreb and then was flown from Zagreb to Sarajevo on a military transport plane.”

The press stayed in one of two hotels. Melhus stayed in the Holiday Inn, which also housed Holbrooke and journalist Christiane Amanpour at times during the siege.

“We had no electricity in the hotel,” he said. “The windows were plastic sheets. Sixty percent of the building was damaged or destroyed. A portion of the fourth-floor stairwell had been blown away and there was no elevator.

“Trolleys ran in front of the hotel, going to the Old Town. One day I was outside and a trolley was stopped right in front of the hotel, but it did not move.

“I asked why it was stopped there and was told a sniper in the hills had taken out the trolley driver.”

Melhus talked to university and city officials.

“Most of what I produced was aired while I was in Sarajevo. I transmitted with a BBC satellite phone system right there in the hotel. The phone bill was $8,000 for one week.

“In those days, we had tape recorders. We put bits of paper into the tape reel to mark the beginning of each sound bite. So I had to do a lot of spooling while on the satellite phone, in order to transmit the content for my stories.”

* * *

During our visit, we drove into Sarajevo and down the main street and stopped at the Holiday Inn where Melhus had stayed. We wanted to see how the hotel had been rebuilt. As we walked into the lobby we were stopped abruptly by a guard who told us the hotel was closed. He would not tell us why, but quickly escorted us out the door.

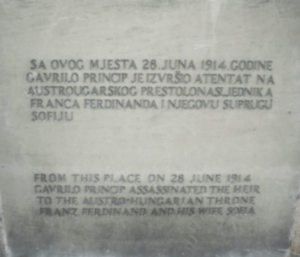

A few blocks down the street was The Hotel Corner, right across from City Hall, which Hapsburg Archduke Franz Ferdinand visited before he was assassinated in 1914.

Melhus asked the receptionist if the Republic of Srpska had been just across the river that flows along the street in front of the hotel.

“Oh, no. I’m Bosnian,” she said, not understanding the question.

With further discussion we learned that the hotel was in the Bosnian portion of the city, across the river from what had been the Republic of Srpska.

* * *

“I am from Srebrenica,” she later told us. “I was only 14, and 8,000 of our people were killed by radical Serbs.

“Not all Serbs are bad,” she said. “The trouble was caused by radicals.”

“My grandfather and father went to the forest to hide, and their bones were found later.

“My father was shot in the temple. So he did not know he was a target. He did not see his killers, and he died instantly.

“I feel worse about my grandfather because they blindfolded him and shot him from behind.

“My father was 40 years old, and my grandfather was 70.

“But my father would be happy because both my brother and I finished college, my brother in biology and me in economics.”

The economy of Sarajevo is still challenged.

The best job she can get is a hotel receptionist, even though she has a college degree in economics.

“Perhaps it is my bias as a Bosnian,” she said, “but Dutch soldiers were not helpful to those of us who were civilians. One Dutch soldier told a friend of mine that Serbs had a right to kill Muslims.”

In July 1995, Dutch U.N. peacekeeping soldiers in Srebrenica failed to prevent the town’s capture despite the fact that the U.N. in April 1993 had declared the town a “safe area” under U.N. protection.

* * *

As we walked through the old city, we went by one park after another with graves and monuments to the estimated 10,000 who died during the conflict. The city had endured the longest siege of a capital city in modern warfare.

The next morning, we drove by the Olympic stadium for the 1984 Winter Olympics. The green space to the south of the stadium was filled with gravesites.

The memorials to the conflict in the Balkans are everywhere.

Will Norton, Jr. is the dean of The Meek School of Journalism and New Media. Article courtesy of Meek School Magazine.

For questions, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…

Recent Comments