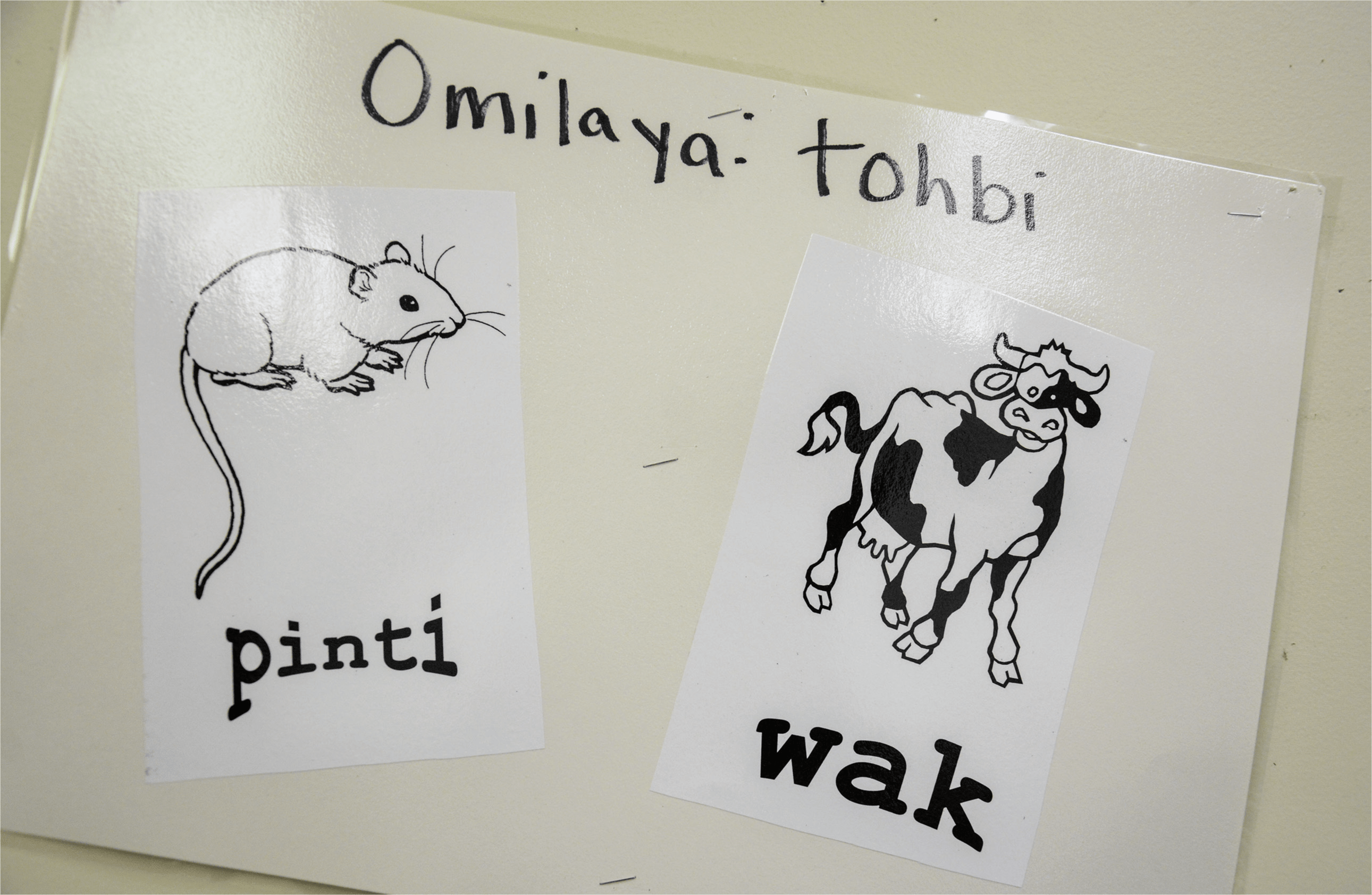

Inside, laminated posters of Choctaw words like “Halito” (hello) are stuck to wood paneled walls, and an assortment of mismatched chairs make a square around the room.

The Choctaw language classroom at Choctaw Central High School is not by any means modern, but teacher Farrell Davidson does the best he can with what he has to preserve a dying language.

Davidson begins by addressing each student in Choctaw, a language that to an outsider is almost impossible to describe, other than fast and rhythmic.

Some of the more advanced students answer him with ease, while others meet his questions with wide, blank eyes, like baby deer caught in headlights.

Neshoba leans back in his chair, a sly smile on his face as he pointedly responds, “I know what you’re saying, but I don’t want to answer.” According to Davidson and other Choctaw elders, this is precisely the problem.

Davidson is on the front lines of a battle Native American tribes across America are waging with varying degrees of success. As the outside world encroaches on what were once fairly isolated communities with few resources, native languages are slipping away as youth become more interested in what lies outside the reservation. It is an uphill struggle, trying to engage students in a difficult language that is being spoken less and less at home.

Once a tiny band relatively detached from outside society, the Mississippi Choctaws managed to maintain fluency for longer than most. As late as 1990 many members of the tribe spoke the language frequently. However, as time passed and industry moved in, English slowly became the first language of the younger generations.

Now, before it is too late, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is on the offensive to preserve what remains of their native tongue, wary of the sad example of other tribes who have all but lost theirs, and with it, a sense of their culture.

The question now is not why to save an imperiled language, but how.

In order to preserve it in its entirety, the language would once again have to become the first one spoken by most tribal members. But that is no small feat, trying to convince an entire generation to switch English, their first language, for an ancient tribal tongue that many have only begun learning in their teens.

It is like asking a group of high school students at most any other school in America to stop speaking English and switch entirely to Spanish, a language they have only studied for two or three years, tops.

The key, according to North Carolina State University linguistics expert Walt Wolfram, is to find a way to give the children a sense of identity attached to Choctaw.

“The fact of the matter is it is not needed economically,” Wolfram said. “It is not needed for social advancement. It doesn’t really have the socioeconomic base in terms of its motivation that other languages do. That has to be compensated for by really strong connections with identity so that little kids have to think, ‘This is who I am. This is my language. This is my own language,’ and so forth.”

Farrell Davidson understands this better than anyone.

“I always look at, for our tribe and our language, everything from a traditional point of view,” he said. “It’s understanding the full history of our tribe, and trying to retain our language, trying to get our students to be proud of who they are. You can still do that with this society and this world… Anyone can play stick ball, anyone can make baskets, but our language is what gives us the distinction of who we are from any other tribe.”

In Davidson’s opinion, his students do not resist Choctaw out of laziness or apathy, but rather from an adolescent fear of not conforming in an outside world that values fitting in.

“It’s not resistance, but getting them to see that it’s good and proud to speak your own language. It’s not something to be embarrassed about; it’s nothing to be shameful about. That you can do it and… deal with this part of your life and also what you’re living in this part with this other society, you can still do

both, and you can still retain them,” he said.

“They haven’t grasped that concept just yet,” he said. But he is optimistic that they can, and once they understand they won’t be so skittish about what the world thinks.

Children and teenagers are not the only ones who need a crash course in Choctaw. Their teachers do too. Or rather, their teacher assistants.

There is a noticeable lack of Choctaw instructors in tribal schools – only one at Choctaw Central. However, many assistant teachers are tribal members, and like the youngest generation, seem to have lost much of the native tongue of their ancestors.

This is where the language program organized by coordinator Roseanna Thompson comes in. Held once a month at Choctaw Tribal Schools headquarters, it tries to help employees achieve enough proficiency to adequately teach Choctaw.

This month’s lesson includes crafting stickballs. Stickball is a traditional tribal sport, roughly similar to lacrosse, only more ardently aggressive, and decidedly more dangerous. The balls, not much bigger than a golf ball, are hand crafted and woven together using leather string.

Today, the class resembles a mixture of Farrell Davidson’s conversational methods and an elementary art program.

Balls of painter’s tape are scattered precariously around the tables, and groans of frustration can be heard as students realize they have woven their balls in the wrong direction.

The teacher’s assistants have grouped themselves together by age, chitchatting amongst themselves in English, except when asked a question by one of the instructors.

“We’re doing a lot with the mixture of immersion and conversation, and we do a lot of hands on. When they’re making the stickballs, we walk around and ask them what they’re making,” Thompson said.

“What is leather in Choctaw? When you weave a pattern, how do you say that in Choctaw? They’ve learned the words, and they’ve learned to make a sentence, like if I ask them, ‘What are you making?’ They’re going to say, ‘I am making a stick ball,’ in Choctaw, which they couldn’t do before, so they’re learning how to do that,” she said, glancing over her shoulder at a table of young assistant teachers who have a tendency to get distracted.

When asked why even young educators are so wary of speaking Choctaw, Thompson says her students regret that they don’t already know the language.

“The younger generation, some understand the language, but they can’t speak it,” she said.

“That table,” Thompson points to the same group of young women in the back, who are giggling loudly now, “they don’t understand it, and they can’t speak it, so they are resistant because they feel like they should have learned it, and they hate it that they don’t know it. They’re impatient with themselves, I would say. They say, ‘Oh, I’m supposed to know this. I need to be on it now.’ They get frustrated.”

There are still some young, native Choctaw speakers, such as Stacey Billy, an artisan for Choctaw Cultural A airs. Billy, an expert in crafting hand carved wooden clubs, or “rabbit sticks” for traditional hunting trips, learned Choctaw as his first language. He says he makes a point of speaking it at home with his wife and stepdaughter.

“I think it basically boils down to family. How much ever your family speaks Choctaw to you is how much you’re going to learn and try to use it in the household,” he said.

Billy tries to teach his stepdaughter as much Choctaw as possible while she is still young. After all, the older you get, the harder it is to learn a language.

“I try to throw some words in there when I’m talking to her. Like when you say, ‘It’s time to eat,’ I say the English ‘time’, but I say ‘Time to ipa.’ They do pick up on it. I hear her say it. You get a certain satisfaction out of it because you know that you’re passing it on,” he said.

It is possible that the most important opinions come from the students themselves. In the end, they must decide whether Choctaw means enough to them to preserve.

Back at Choctaw Central, five tenth graders gather in the library. They are all “Mikos” (chiefs), or honor roll students in Farrell Davidson’s class. But despite being star students, all but one say they only speak a few words of Choctaw a day at home. When asked why some of their fellow students are hesitant to speak the language, they say they are embarrassed. Like all adolescents, they fear criticism from their elders and their peers.

“They get scared. You laugh at them and they get scared. Personally, whenever I try I mess up here and there,” said one student.

“It’s really tough,” adds another.

According to Davidson, it is not characteristic of the Choctaw to ask questions.

“I call it a generational gap,” he said. “You just don’t ask questions because you are expected to already know.”

Every language learner knows it is impossible to master a language without asking questions. Learning is all about trial and error. It is frustrating, emotional, and often embarrassing. In an environment where mistakes are frowned upon, it is easy to see how Choctaw students could resolve to just leave the language alone.

“I went through that, and I try not to put that on them,” said Davidson.

“I tell them to ask questions. I will share it with you. I’m not going to school you. I said, ‘We used to ask questions but we got schooled.’ We got told, ‘You should already know your Choctaw.’ I’ve argued with even my mom and my aunts about that this generation has to change a little bit.” I said, “You want them to maintain it, you’ve got to let them ask questions. You’ve got to want to share it with them.”

It is not a question of whether or not these students want to learn Choctaw. They are smart and determined. They each have unique goals that stretch far outside their small Mississippi town. Respectively, they aspire for careers in neonatal nursing, engineering, the National Guard, pathology, and criminal justice.

However, they all share one thing in common: they want to leave the reservation.

“I want to explore the world,” Teegan smiles. All of the students nod in agreement.

“My mom. Our elders. They tell us to go, because (the reservation) … It’s always going to be here.”

And that is perhaps the biggest challenge for the Choctaws. And for Farrell Davidson.

If the best and brightest leave, who will be left to carry on the legacy of the Choctaw?

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw and Choctaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Recent Comments