By Molly Minta

Mississippi Today

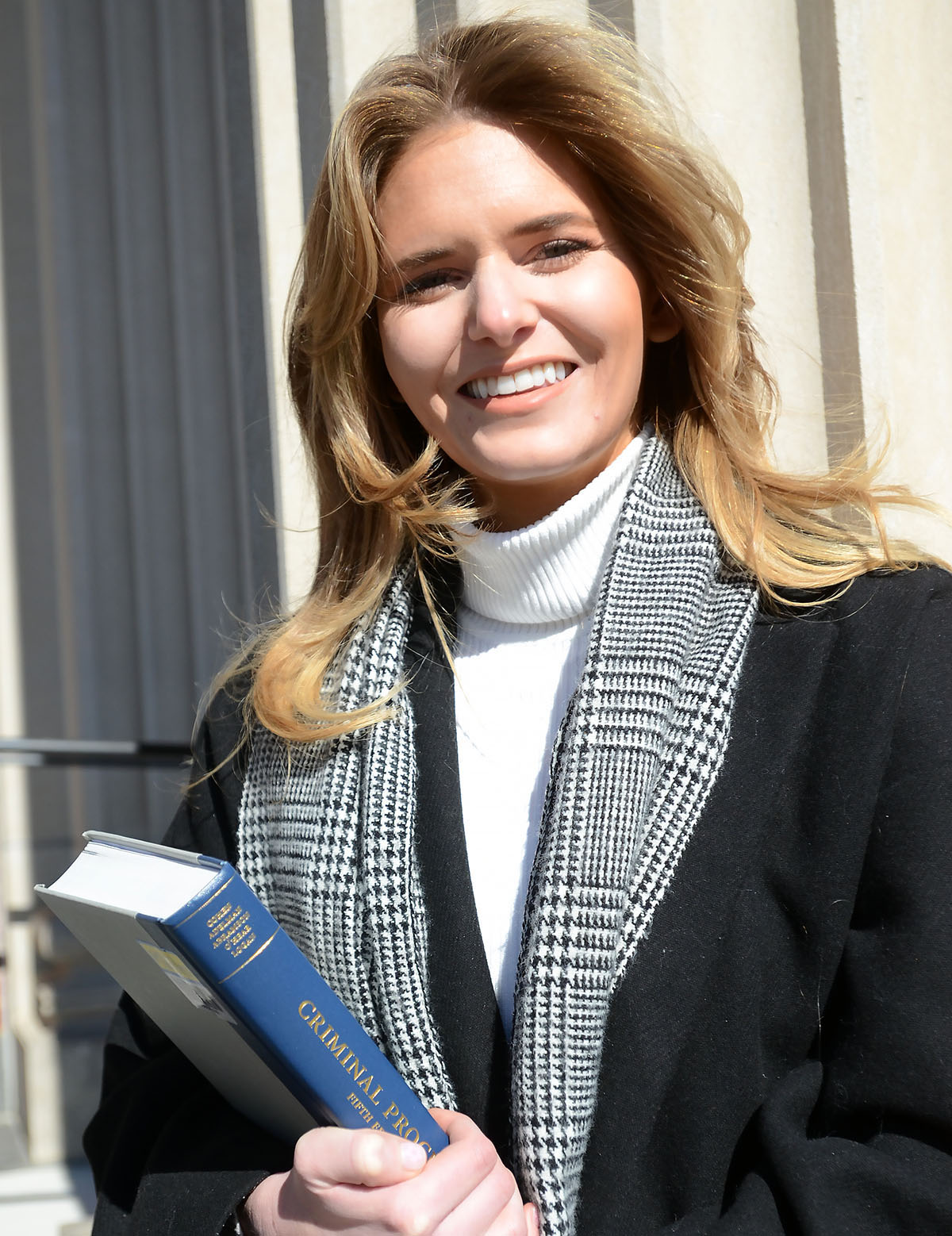

Brittany Murphree was born and raised in Rankin County, Mississippi, one of the most Republican counties in one of the most Republican states.

She went to Northwest Rankin High School where she was the president of the school’s chapter of Teenage Republicans of Mississippi. She interned for Republican Gov. Phil Bryant, and her parents voted for Donald Trump twice (she did too, one time). At the University of Mississippi Law School, where Murphree is now in her second year, her friends are mostly conservative white people.

In early January, Murphree shocked them all when she announced that one of the courses she was taking this semester was “Law 743: Critical Race Theory.”

“Why would you take that class?” her dad vented on the phone. “It’s the most ridiculous concept.”

“Brittany, that class is just gonna make you feel so guilty about being white,” some of her classmates warned.

“You’re gonna get canceled.”

Their tone was teasing, but Murphree thought they sounded genuinely worried. She understood why. Critical race theory had become a flashpoint of national politics in 2021 as conservative media latched onto the term, deeming it “hostile, academic, divisive, race-obsessed, poisonous, elitist, anti-American.” In speeches, both House Speaker Philip Gunn and Gov. Tate Reeves had vowed to ban the theory from being taught in schools. Murphree didn’t know much about critical race theory, but she knew some people in Mississippi thought it was taboo.

Still, Murphree wanted to know what the “hotly debated topic” was really about. “Law 743: Critical Race Theory” is the only law class in Mississippi solely dedicated to teaching the high-level legal framework. To Murphree, the class seemed like an opportunity — one she might not get again.

“I’m either gonna completely agree with this, or I’m gonna be able to say, ‘No, this class is terrible,’” she told her friends. “The best way to have an opinion about this class is literally to take it.”

“Critical Race Theory: Law 743” is an unusual course at the University of Mississippi Law School, where most classes teach students about the law or how to argue like lawyers. What makes Law 743 unique is that it teaches a bird’s eye view of the legal system, a framework for understanding the law and its impact on racial minorities. Law 743 is also more diverse than many classes at UM’s law school. In the 13-person class, Murphree is one of four white students.

Out of all her courses this semester, Murphree was the most anxious to see what Law 743 would be like. On the first day, the professor, Yvette Butler, issued a disclaimer that Murphree took to heart. Critical race theory, Butler said, examines difficult and potentially upsetting topics, but it was important that the class remain a safe, respectful space. Students were going to disagree with the readings and with each other; when they did, Butler asked them to give each other “radical acceptance.”

When Murphree started her readings later that day, she pushed herself to keep an open mind. One of her first assignments was a 1976 article by a professor at Harvard Law School named Derrick Bell, who is often credited as the founder of critical race theory.

In the article, titled “Serving Two Masters,” Bell lays the groundwork for one of his most notable arguments: By and large, school desegregation was a failure. Brown v. Board of Education, he argues, was in many ways harmful to Black communities across the country. As Black schools closed, Black teachers, principals, bus drivers and custodians lost their jobs. Bused to white schools, Black children were more likely to be beaten, arrested, and expelled than their white peers. As a lawyer for the NAACP, Bell had sued for desegregation; in “Serving Two Masters,” he was wondering if that was the right tactic after all.

Murphree found the article astonishing. She had thought critical race theory was focused on critiquing the actions of white people, not scrutinizing the decisions and tactics of Black civil rights attorneys. She found her other readings just as surprising. Lawmakers were wrong to call critical race theory “Marxist,” she learned, because the framework was actually a rejection of legal theories that had centered class and sidelined race.

She was excited by what she was learning, and she wanted to share it with her peers. That Wednesday night, at a law school mixer at a bar near the Square, she started chatting with her conservative classmates about how the readings weren’t like anything she’d thought.

“Am I gonna regret talking to you about this?” a classmate joked.

During the second day of class on Thursday, Butler asked students to evaluate Bell’s argument in “Serving Two Masters.” On a PowerPoint slide, Butler wrote: “How does Bell characterize the Brown decision? Do you agree with his characterization?”

Teresa Jones, a second-year law student in the class, raised her hand. While she understood Bell’s argument, Jones said her life experience gave her a different perspective. She had grown up in a Black working-class family in unincorporated Sharkey County in the Mississippi Delta. Her mom worked the trim table at the catfish farm, and her dad was a military veteran and an HVAC technician. When they were young, there was just one high school in Sharkey County, and it had been the school for white children.

Brown wasn’t as harmful to the Black community in rural Mississippi as segregation had been, Jones said. If anything, Brown was the only reason her family had a school to go to at all.

“There were people who weren’t going to school at all before desegregation, like literally going to school in a church,” Jones said, “and that was only part of the time because they had to go chop cotton.”

The goal of the class is not to change minds, but to introduce students to critical race theory and how to apply it to the law, current events and issues in popular discourse, Murphree said. To that end, the class has talked about racism and how to define it, the idea of color-blindness, and the difference between equity and equality. They also learned about “interest convergence,” a core tenet of critical race theory that argues communities of color only achieve progress when white communities also benefit. Interest convergence, Jones said, helped her better understand why the Mississippi Legislature voted to change the state flag in 2020 — because “they were about to lose a lot of money with the NCAA.”

The longer class was in session, the more Murphree felt like everyone was opening up and saying what they really thought. Before class ended on Thursday, one of Murphree’s white classmates asked what was the better term: “Black” or “African American”?

Murphree was initially unsure. “Are we about to disagree on this?” Murphree thought. “Are they gonna be offended that she just asked that?”

Butler, the professor, asked the Black students in the class to each say what they preferred. Jones didn’t think much of the conversation; she had already thought about why she preferred to call herself “Black” years ago in undergrad. But for Murphree, the discussion was enlightening. Another Black student in the class pointed out something she had never before considered: “We don’t call you white Americans.”

On Friday, Jan. 21, Murphree was about to start her homework when news broke that the national debate over critical race theory had finally come to Mississippi. The Senate had passed Senate Bill 2113, one of several bills this session that aimed to ban discussion of critical race theory in K-12 schools and universities.

Murphree read the bill in disbelief. “The party I associate with,” she concluded, “just doesn’t even know what the truth about this class is.”

The more Murphree thought about the bill, the angrier she got. In just two weeks of taking Law 743, she had been introduced to ideas she never before considered. She learned there were activists and academics who were critical of school integration and the way it had been enforced. She gained a new perspective on racial progress in America. And she still had a whole semester left of issues that no longer felt intimidating but urgent to learn — implicit bias in policing, affirmative action, and reparations.

“Why are they so fearful of people just theorizing and just thinking,” she thought. “We’re not going to turn into, like, communists. Y’all chill out.”

That Sunday, Murphree watched the footage of the Senate vote to pass SB 2113. As every Black senator in Mississippi walked out of the chamber in protest, Murphree decided that she, too, would take a radical step, one she knew would likely end her dream of working in local Republican politics. She opened up a Microsoft Word document and started writing.

“To date, this course has been the most impactful and enlightening course I have taken throughout my entire undergraduate career and graduate education at the State of Mississippi’s flagship university,” she began.

“The prohibition of courses and teachings such as these is taking away the opportunity for people from every background and race to come together and discuss very important topics which would otherwise go undiscussed.

I believe this bill not only undermines the values of the hospitality state but declares that Mississippians are structured in hate and rooted in a great deal of ignorance.”

She asked a friend who works in the state Capitol to read it over. Then she addressed the letter to all 27 members of the Mississippi House Education Committee, attached it to an email, and hit send.

As written, SB 2113 is vague enough that Law 743 could likely still be taught. The bill, authored by Sen. Michael McLendon, R-Hernando, would prohibit schools from compelling “students to personally affirm, adopt, or adhere … that any sex, race, ethnicity, religion or national origin is inherently superior or inferior.”

That’s not happening in Law 743, or in any public schools in Mississippi.

“Nobody is saying, ‘Dear white child, you are inherently superior to dear Black child,’” Jones said. “No one is saying that. If anything, that is something we’re trying to deconstruct.”

Murphree hasn’t heard back from any of the lawmakers she sent the letter to, but what happens next to SB 2113 is now up to the House, which has until March 1 to take up the bill. Though several more detailed and far-reaching House bills died in committee, representatives could try to make SB 2113 stricter.

If the Legislature successfully banned critical race theory, Jones said it would be a detriment to the academic environment at UM’s law school. The class has helped her understand her own opinions better and argue for them more effectively — what law school is supposed to be about.

“There are some things in critical race theory that I disagree with and (Professor Butler) said, ‘Well that’s OK, it’s a good thing actually,’” Jones said. “We should be discussing these things and saying I agree with this, I don’t agree with this. That’s OK, that’s what open discussion is about.”

Murphree said it has been frustrating to see fellow conservatives twist critical race theory into something it is not. But she also gets why they might be afraid of thinking about the issues at the heart of the theory. They don’t want to feel “white guilt,” especially not in Mississippi where many white people can easily trace their lineage to slave-owners.

“Here in the Bible Belt, people ride on the fact that they’re a good person, they go to church on Sunday, they give money to the poor, so they could never imagine being called a racist,” she said.

But the younger generation in Mississippi is more perceptive than conservatives tend to give them credit for, Murphree said. Children will always be able to see how racism organizes society, even if their teachers are banned from talking about it. Murphree grew up seeing it; critical race theory just gave her a way to talk about it.

At Northwest Rankin High, “I could just look around and see people in my class, and I could see the racial divide and how people literally said the n-word,” Murphree said. “Nobody had to teach me things. I saw it in my life.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Recent Comments