Bradley Alex couldn’t understand why his wife was so upset with him. The young couple had just had their second son but she was edgy, emotional, high strung. It wasn’t like her, and they both knew it. But why?

After pleading and asking, “What’s wrong?” as so many husbands do, Alex and his wife finally got an answer 30 or so years later from a television special: postpartum depression.

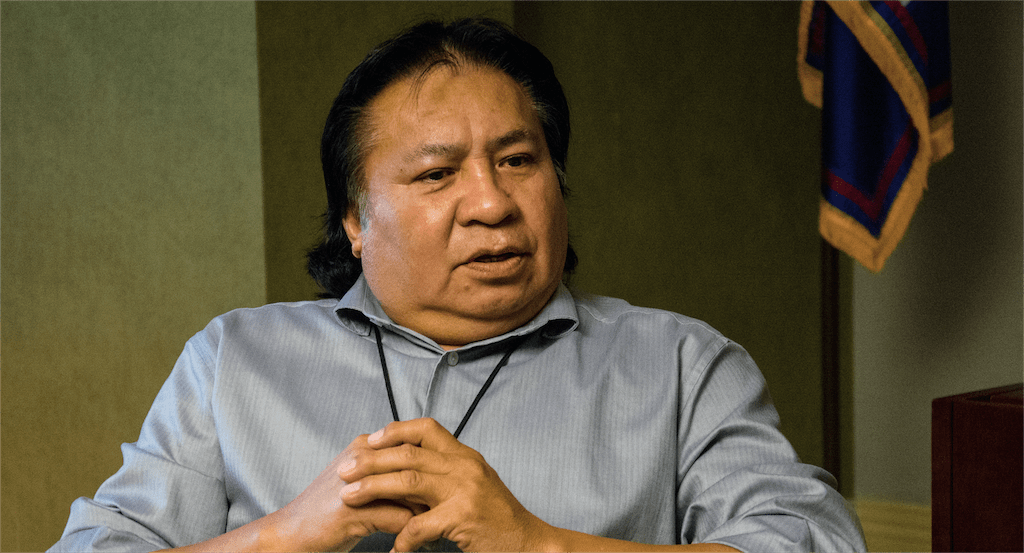

Today, Alex looks back at that tough period in his life and is thankful for what he now realizes was valuable training for his current job as judge of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians Peacemaker Court. He recently handled a case between spouses and found the new parents’ arguments sounded all too familiar. Sure enough, a doctor confirmed his diagnosis—postpartum depression. Case solved, problem resolved.

Peacemaker Court is radically different from the American court system, which seeks to punish the guilty and generally declare one side right and one side wrong. Often, the Choctaw feel, that approach can increase frustration and animosity on both sides.

Peacemaker Court seeks a different kind of justice, one with roots deep in Choctaw tradition. It concentrates on bringing the two sides in a dispute together. Instead of blaming, it aims to heal and restore broken relationships.

Now, when couples come before him, Judge Alex thinks back on his own marriage and the confusion he felt when his wife was sick and didn’t realize it. “I thought she was just going crazy on me. I’m 60 years old and a lot of stuff I have gone through—I believe that there was a purpose for me that I went through those in life. That’s the peacemaking court. It’s something that’s wonderful,” he said.

His occasional broken English can’t mask his wisdom. That wisdom and an intuitive understanding of people came from a long history in law enforcement.

“I’ve dealt with people throughout most of my adult life,” Alex said. He was a probation officer for 17 years, and before that a police officer. But not a no-nonsense, ticket-writing, authoritarian police officer. Alex gave people rides home after he arrested them, went to check on them days later, and even prayed with them.

“Other officers, they didn’t really like that. But I said, ‘This is our community. These are our people, and you have to care for your people.’”

Step inside the peacemaker courtroom, and it’s nothing like the stern standard closing scene of Law and Order. The courtroom is circular, with one large wall that has no corners.

A smaller circle of chairs sits inside, creating an informal setting in which disputes can be resolved. Judge Alex sits among the plaintiffs and defendants, rather than looking down on them from a raised bench. In fact, “judge” may not be the best word to describe him. He is more like a mediator.

‘Itti-kaña-ikb’ is the Choctaw name for the court. It means “making friends again.” The cases that come to Peacemaker Court are handpicked from the tribe’s civil, criminal, and youth courts. The referrals are usually family cases —divorce, child custody— that authorities believe can be resolved without formal court proceedings. But this is a one-time-only opportunity. It’s informal and inexpensive, and no lawyers can be present — only the judge and the opposing parties.

If cases don’t succeed in Peacemaker Court, it’s usually because someone is unwilling to cooperate with the process, or if they demand an attorney. If so, the case is sent right back to the court it came from, and normal legal proceedings occur. It doesn’t happen very often.

Judge Alex is full of stories about people he has dealt with in the court and how successful it has been for them. One would think he’s been doing this for years, but he’s just finishing his first.

“The court is aimed at honesty,” Alex says. “They admit their guilt and that they want to proceed in the court… that they want to settle it and talk to the victims.”

Most of the cases involve domestic violence. But they aren’t always typical scenarios. Alex talks about a case in which a son was abusing his father. Through peacemaking sessions, he discovered that the son held his father in contempt for calling him a loser after dropping out of school. Both had scars from all of the abuse, and Alex described “uni-brows of anger” across their foreheads.

He patiently coaxed them through the principal steps of peacemaking—guilt, forgiveness, and acceptance. Alex later bumped into the pair as they shopped for groceries for the son’s wedding feast. “Everything worked out good. I see them now with a smile, but they had

a uni-brow,” Alex said.

Alex offers a simple recipe for success — communication.

“It’s talking. It is just talking. You can overcome anything. Communication. I’m telling you.”

He begins by talking to the parties separately. Then he brings them together and talks to them and any key people involved. By then, Alex says they will have unearthed the real problem, whatever it is that has caused the anger or contempt bubbling up inside.

“When we settle cases here, we talk about what led up to this. Even sometimes we go back to their childhood. How were they raised? What kind of family? What is it? They bring it up. Eventually they find where that affected them,” Alex said.

And then, the process of puzzling broken pieces back together begins.

Alex tells of a young boy who was destroying property at his mother’s home — her car, their mailbox. He was arrested and sent to appear before the youth court. Then the case was transferred to Alex. But the boy wouldn’t speak to anyone.

So Judge Alex started talking on his own.

“I said, ‘How old are you?’

“He said, ‘14.’

“I went back to my childhood and told him the first time I had a girlfriend I was 14. I had a crush on her so bad that when we broke up, I felt like my stomach was all knotted up and everything and I just couldn’t sleep.

“That’s when his head went up. He said, ‘You did, too?’”

It turned out the boy’s father was remarried and living in another town. His mother was raising him and his two sisters. He felt alone. His love life was in shambles, he felt he had no one to talk to, and his emotions exploded into violence.

“He said, ‘Nobody understands, but you do.’ I said, ‘Yeah I went through it.’ A lot of us went through that and are still going through it.”

The judge explained to the boy that he could talk to his mom about what he was going through and should apologize to her. That like him, she had a broken heart.

“He said, ‘With Dad?’”

“I said, ‘Yeah.’”

Just as Alex followed up with people he arrested as a police officer, he kept in contact with the young boy after resolving the case. He asked him to help install insulation in Alex’s home and paid him for his time. “That’s the only thing he needs is a father figure. These young men, teenagers that don’t have a father, I went through that,” he said.

For Alex, the case hit close to home. Alex’s own father died when he was 9. Then, as a young man, his stepfather was abusive. To get away, he joined Boy Scouts, Cub Scouts, “whatever club I could get into.” He too, had no adult in his life to confide in.

“A lot of stuff that I went through, I see these people going through. I love my people. You have to love your people in order to be in a position like this,” he said.

As Alex describes the cases of the past year, he makes the process seem simple, or just common sense.

He prefers the Choctaw way over the American legal system any day. In American civil and criminal courts, “the whole truth is not spoken. Both sides do not really give the full truth. Attorneys represent them and I’ve seen that. I was sitting in there. I didn’t like going to see a trial. I’ve seen it and it destroys family. Basically, it destroys the community. When they leave, sometimes people, one or the other or both, are hurt,” he said.

It helps that the tribe is no larger than it is. “Our tribe is small,” Alex said. “I think [the peacemaking process] can affect anyone anywhere. It’s bringing family back together, or the community back together. The other legal system isn’t.”

But as Judge Alex knows, it takes follow up. A problem cannot always be solved with the bang of a gavel.

After all, fines, jail time, or retribution won’t heal a wounded soul.

By Kate Hayes. Photos by Ariel Cobbert.

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw and Choctaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.