By Allen Boyer

On Monday morning, October 1, 1962, in his office in Washington, Robert Kennedy said it had been the worst night of his life.

On the campus of the University of Mississippi, it was worse. Two men were dead, one building was wrecked, and the stately façade of the Lyceum, the center of the campus, was scarred with brickbats and bullets. Wisps of tear gas lingered. Anyone driving on campus – and not many people were – stopped for MP’s at checkpoints and drove past overturned burned-out wrecks of cars.

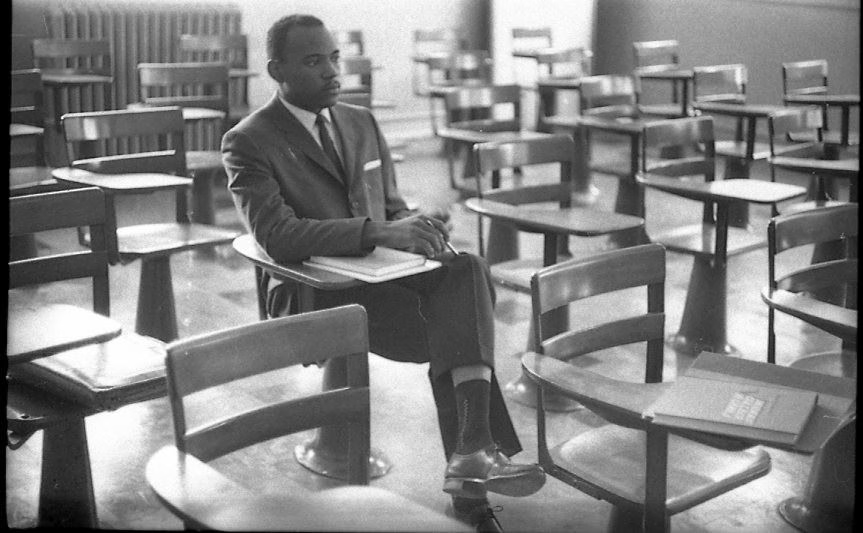

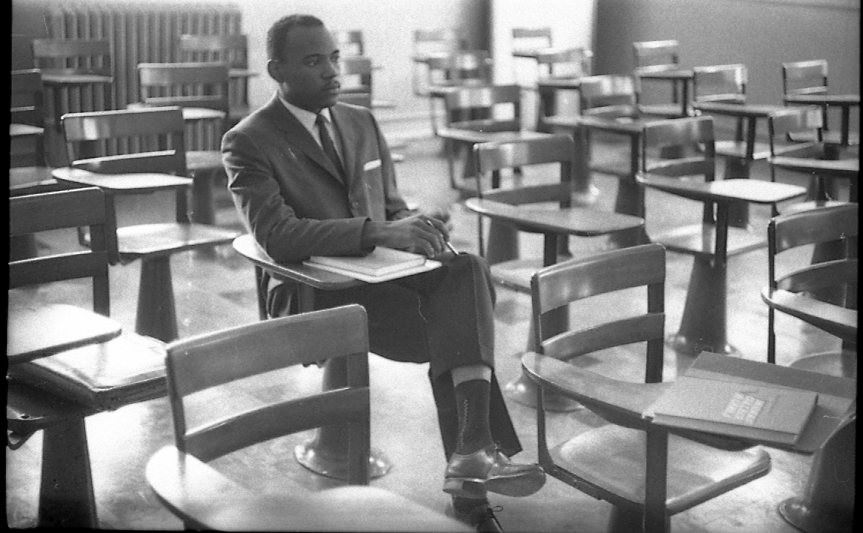

At dawn that day, the city of Oxford, Mississippi, counted six thousand people. Stationed around Oxford, that morning, were the spearheads of fifteen thousand soldiers – 20,000 infantry and paratroopers, the rest from the Mississippi National Guard. Ole Miss had fewer than 5,000 students. One of them was black: James Meredith, over whose enrollment the students had rioted and the soldiers had deployed.

The Battle of Oxford, it has been called, or the Meredith Incident, or the Last Battle of the Civil War. At Ole Miss, 60 years later, it is still called the Riot.

The first good book on the Riot was by Walter Lord, who had written about the Titanic. Lord’s book on the Riot was “The Past That Would Not Die” (1965). Lord knew about chaos and darkness; he had written about the Titanic. He looked past the Riot to what had caused it, the poverty that locked in racism and the willful stubbornness with which too many Mississippians held to the past.

In 2009, in “The Price of Defiance,” Ole Miss historian Charles Eagles told the story from within the university – starting with Jim Silvers, the brilliant gadfly professor, and focusing on the enigmatic energy with which Meredith chose to set larger forces in motion.

And Meredith has told his own story, too, in “Three Years in Mississippi” (1966) and “Me And My Kind: An Oral History” (1995).

Kathleen Wickham, who teaches journalism at Ole Miss, marked the 55th anniversary of the Riot with a forceful and memorable book: “We Believed We Were Immortal: Twelve Reporters Who Covered the 1962 Integration Crisis at Ole Miss.” Wickham profiled a dozen of the reporters and photographers who came to Oxford to cover the Riot. Her subjects’ words – the stories they filed, the memories they shared – give an intense, troubling portrait of that landscape.

Claude Sitton reported on the Riot for the New York Times. He filed a long story, perfectly phrased and paced, an exemplar of Times “Gray Lady” style.

“James H. Meredith, a 29-year-old Negro, was admitted last night to the University of Mississippi campus,” Sitton wrote. “A riot broke out shortly after his arrival … Students gathered in ‘The Grove,’ a tree-shaded grassy mall in front of the Lyceum building, a neo-Greek revival building, as the marshals arrived.”

No one who read Sitton’s article would have known that he favored a roughed-up, dirty shirt for covering riots, or that he had rolled underneath a car to get out of the melee. Nor would they have guessed that he was a friend of Karl Fleming, a reporter of the two-fisted old school. Fleming drank whiskey and smoked unfiltered Camels, and the prose he supplied to Newsweek was muscular: “The resistance fighters arriving were rough-looking Snopesian characters, many with angry faces and sagging bellies in a variety of working clothes.”

The afternoon that the Riot broke out, I was a month into first grade. My father taught at Ole Miss, in the School of Education, and we lived on campus, in one of the white frame houses that the university rented to faculty. (Oxford, then, was not a place of subdivisions and condominium blocks.) In mid-afternoon, we drove around the Grove and past the Lyceum. The students were milling about; a crowd was standing in the street, parting for us as we drove slowly through. The mass of people caught my attention. It was the first time I had seen a crowd, and it was the first time I saw a mob.

On the steps of the Lyceum, the marshals were arrayed like medieval soldiers – ranks of stout men, with helmets and flak jackets and batons. The crowd of students had been pulsing and shifting. The ranks of the marshals were quiet and they kept formation. They were almost as calm as Claude Sitton would suggest. As dark came on, that changed.

CBS newsman Bob Schieffer drove a radio truck in from Fort Worth, just in time to be surrounded by rioters. They mobbed him. They smashed his tape recorder, and he hit the dirt as a sniper fired. “The next twelve hours,” he summed up, “were the most terror-filled in a long life of covering not only Vietnam but countless protests that turned violent.”

Curtis Wilkie, who was then a senior in the Ole Miss journalism school, sketched a map on a page of his spiral notebook. Area of most fighting, he wrote of the spot where flowerbeds faced the Lyceum. Wilkie kept writing. He jotted down events and landmarks and produced the best précis of the night. Initial tear gas attack. Fire truck captured. Chemistry building (radio reporters) attacked 11 pm. Car burning. Confederate monument. Barricades and car burning. Radio mobile unit destroyed and burned. (Was that Bob Schiefer’s gear?) Oxford boy dead 9 pm. Newsman dead 8 pm.

In the Circle, students were raging – yelling, pitching bottles, hurling brickbats. The marshals held their line, dodging, firing back with clumsy tear-gas guns.

Late that night, a telephone call came from one of my parents’ friends. He worked in the biology department, he was concerned about his lab rats, and he had a question: which way was the tear gas blowing?

My father the education professor and our neighbor Mark Hoffman the music professor walked up the hill. At the top was the Grove. All the streetlights had been shot out. In the darkness, people ran past, then tripped and went sprawling; the Grove was ringed by an obstacle, low wooden posts connected by chains. Anyone who tripped was someone from outside town – students would have known about the posts and chains.

My father and Dr. Hoffman walked into the Grove. They were a quarter-mile from the Lyceum, which they thought a safe distance. They could hear shouting and swearing and gunshots. They talked nonchalantly with a young man who was brandishing a monster-sized hunting knife and said he had brought it there to kill somebody. They could not tell which way the tear gas was blowing.

My father had heard that the military police on their way to town were from the 82nd Airborne Division. He knew the 82nd from Fort Bragg, from his time in the Korean War, and he thought the 82nd could handle this. He and Dr. Hoffman walked back downhill and home.

Closer to the fighting was another family friend: Evans Harrington, the handsome, courtly writer and Faulkner scholar. At the eastern margin of the edge of the Circle, he realized how bad it would be. “Things started whizzing by my head and hitting that car,” Harrington wrote, “and I realized people were throwing rocks and concrete at it, and I hit the ground as quick as I could because I was scared I would be hit, and watched that crowd of marshals.”

Michael Dorman interviewed John Faulkner, William’s brother, comparing Lafayette County to Yoknapatawpha. Dorman would have found Faulknerian conflict in front of the Lyceum that night. The family’s tradition holds that John’s son Jimmy drove a commandeered bulldozer toward the Lyceum that night, to be stopped by John’s other son Chooky, a National Guard captain serving alongside the marshals.

Meantime, at the YMCA on the Circle, a third relative ran a makeshift infirmary:

“Social activities coordinator Louise Meadow, William Faulkner’s sister-in-law, was pressed into service tending to bloodied rioters and injured newsmen. Rioters seeking bottles for Molotov cocktails had cleaned out the soda machine, and there were no medical supplies in the facility. Meadow used paper towels as bandages.”

Sidna Brower, a young lady from Memphis, covered the riot from her editor-in-chief’s desk at the Daily Mississippian. She wrote an editorial denouncing violence, then hurried to her room at the Kappa Kappa Gamma House. At Ole Miss, in 1962, women students still lived under an 11 p.m. curfew. The editorial earned her a nomination for a Pulitzer Prize.

As the mob surged toward the Lyceum, French reporter Paul Guihard told his photographer that he would be back in an hour. He vanished into the tear gas floating behind the Fine Arts Building. Guihard was a tall, red-bearded man, and he spoke with a foreign accent. Someone saw him – followed him, or forced him, into a spot that was unlighted and half-hidden by bushes – and then shot him with a pistol, in the back, at close range. Guihard was the only journalist to die covering the civil rights movement. (Guihard’s murder remains unsolved. That does not mean no one tried. For months after the Riot, FBI men stopped by my father’s office, handing him photos and asking him if he recognized anyone.)

The MP’s arrived, and more airborne troops after them. I woke up early that Monday morning, and figured that I would not go to school. Looking out our living-room windows, toward the top of the hill, you could see a line of gray silhouettes, soldiers with helmets and rifles. There were sentries posted on the sidewalk across the street. That afternoon, we drove past the Lyceum again. The burned-out cars looked like huge gray dead beetles. Soldiers were lounging on the grass on the Circle.

For months the town was full of infantry in olive drab, stopping traffic and checking passes.

Shortly after the Riot, the Washington Post sent Dorothy Butler Gilliam to Mississippi. Gilliam was a black woman reporter, the first to work for the Post, and the paper did not want to send her South until the turmoil was settled. Being delayed did not limit her. Gilliam covered the black community, casting light on ordinary people’s fears and hopes. She interviewed a black busboy from the Grill, the eatery in the old student union. After the Riot, in a half-baked reprisal, he was fired by his white boss. “I was glad,” the busboy told Gilliam. “It was a rather small contribution.”

Other white bosses fired black workers. Students who ate with James Meredith or sat with him in class would find their dorm rooms ransacked or bleach poured on their laundry. Newspapers lost subscribers and advertisers; reporters had windows shot out or crosses burned on their lawns. In the end, those small contributions won the struggle for civil rights.

For those who remember the burned cars and brickbats, there is an irony that shadows the manicured Circle and Grove of the present day. The landscaping befits what those acres are: a national historic site, as recognized by the Society of Professional Journalists.

Allen Boyer, HottyToddy.com Book Editor, grew up on the Ole Miss campus. His most recent book is “Rocky Boyer’s War” (Naval Institute Press) and he is currently working on a history of the law of treason. Earlier versions of this essay were previously published by HottyTotty.com and the Phi Beta Kappa Key Reporter.