Sitting in physics class on the Ole Miss campus, staring at a picture of Mount Pumo Ri on his textbook cover, Ryan Waters (BS 98) dreamed of the day he might have a shot at scaling the famed Himalayan mountain range.

“I daydreamed about that picture, and I still have the book,” says Waters, outdoor adventurer and owner of expedition guide service Mountain Professionals.

“At the time, I had never really climbed a big mountain. I had only been rock climbing for a few years, but I’d look at that picture and think how incredible it would be some day to go to the Himalayas. Inside the cover, the caption in the book says many people believe Mount Pumo Ri to be the most beautiful mountain in the world. For some reason, I got this idea that someday I’m going to go climb that mountain, and it kind of stuck with me.”

A native of Marietta, Ga., Waters graduated from Wheeler High School in 1992 and attended East Tennessee State Uni- versity, where he played football for one year before enrolling at Ole Miss.

Once he arrived in Oxford, Waters quickly focused on the geology program. Having an avid interest in all things outdoors since childhood, he believed it would be a good fit.

As it turned out, geology laid the groundwork for the path his career would take.

“I took Geology 101 as an elective my freshman year at East Tennessee,” Waters says. “When I transferred to Ole Miss, they had a more significant program. It seemed like a good idea for a major because I had always wanted to be outside.”

A member of Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity, Waters received a Bachelor of Science in engineering in 1998 and promptly moved back to Georgia to accept a job as a geologist in Atlanta with Black & Veatch, a global engineering, consulting, construction and operations company.

“I worked there for about three-and-a-half years, but the whole time I was there I was climbing more and getting inter- ested in expeditions and high mountains,” Waters says. “I call it my mid-20s crisis because, after thinking a lot over a two-year period, I decided that I had always been interested in working in the outdoors.”

Waters took a chance and began spending his summers working as a climbing instructor for North Carolina Outward Bound School, essentially giving up a full-time formal career as a geologist.

He delved into rock-climbing instructing and backpacking in the U.S., which only deepened his interest in his newfound career.

“I started being more serious about going on my own trips, and that slowly progressed into a couple of years working part time as a geologist and part time as an outdoor educator,” Waters says. “That eventually brought me down to the Patagonia area in southern Argentina.”

Aviva Argentina

Waters moved to Argentina in 2004, where he began working as a mountaineering instructor – a move that would ultimately change his life.

“I lived there a couple of years and really started to pursue mostly mountain climbing,” Waters says. “I started traveling to the Himalayas and all kinds of crazy places and eventually got into guiding more formally as opposed to instructing.”

Doug Sandok, executive director of Paradox Sports, recalls Waters’ steadfast demeanor during their time instructing together in Patagonia.

“He’s a steady hand and doesn’t get bent out of shape about a lot of things,” Sandok says. “He kind of keeps his eye on the ball in a very calm, reassuring way. That’s how he is with his clients too. When he comes into the tent, he’s a very warm personality that people really respond to. He’s also a very driven person that has this tremendous ability to continue to dig deep. Not everyone has that.”

After numerous high altitude climbs and expeditions, Waters had the opportunity in 2003 to summit Mount Pumo Ri, the mountain that had haunted his dreams after first spotting it on the cover of his physics book.

“I ended up climbing that peak, and that was a really cool experience,” Waters says. “I told myself that once I climb this I’m going to take a break for a while, but what really happened was it turned me on to the Himalayas. I was so amazed by that place. Standing on the top of Pumo Ri, I looked across – and there was Everest.”

The following year in 2004, Waters returned to the Himala- yas to climb Everest for the first time.

It turned out to be the first of many trips guiding others through the harrowing trek to reach the peak of the famed mountain.

“It allowed me to suddenly have a good starting point to build a resumé on not only my personal climbs but also moun- taineering guiding companies.”

Within two years, Waters also scaled Cho Oyu, the sixth highest mountain in the world, and had three more Himalayan trips under his belt.

The next climb for Waters was obvious – in Pakistan.

Pakistani Peaks

In 2006, Waters set out for the Karakoram Himalaya in northern Pakistan to attempt climbing Broad Peak, the 12th highest mountain in the world at 26,414 feet (8,051 meters), as well as the infamous K2, the second highest mountain in the world at 28,251 feet (8,611 meters), after Mount Everest.

“That was a significant trip for me because we summited Broad Peak, but we didn’t summit K2,” Waters says. “I was lead- ing the expedition, and the weather had been a little dangerous with rock fall, so it just wasn’t going to happen that year.”

Since that trip, Waters has traveled to Pakistan numerous times and recently returned to the U.S. from his 15th expedition to the Himalayas.

Boulder Bound

In the midst of his many expeditions, Waters found the time to start his own guide company, Mountain Professionals, in 2005 with then co-founder Dave Elmore. Since 2008, Waters has been the sole owner of the Boulder, Colo., based company and continues to lead expeditions and trips.

“We have a list of trips that we offer,” Waters says. “Some people may have an interest in Kilimanjaro, trekking the Everest Base Camp or even climbing Mount Everest. There are people that are looking for an operator and either join one of our trips or set up a private trip.”

While he enjoys leading groups of people on various climbs and expeditions, perhaps his favorite trips are the ones he takes to achieve his own goals and dreams.

And achieve them he has.

Grand Slam

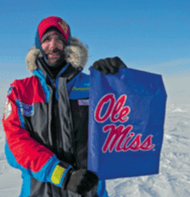

On May 6, 2014, Waters became the first American to com- plete the “Adventurers Grand Slam” unsupported, traveling to both the North and South poles on foot and climbing the highest mountain peaks on each of the seven continents.

“I never really set out to do that,” Waters says. “It just hap- pened. As a mountain guide, there is a lot of business climbing the seven summits, so I just did it by guiding.”

Waters began his ascent to adventurer fame by not only climbing the highest peaks but also by skiing to the South Pole in January 2010 with Norwegian adventurer Cecilie Skog, unassisted and unsupported – without the use of kites or resupplies.

“Cecilie had this idea of trying to ski across Antarctica because it had been crossed a couple of times in various ways but never unsupported,” Waters says. “One other Norwegian guy had crossed it unsupported, but he had used a kite to help pull him across. I was just naïve and said, ‘Yeah, I’ll go with you,’ not really knowing how big of a deal it was. It’s a huge expedition that took us 70 days to complete.”

The duo became the first to ever ski unsupported and unas- sisted across Antarctica via the South Pole.

Waters suddenly realized the only thing left to do to be the first American to complete the Adventurers Grand Slam was to ski to the North Pole unsupported, a treacherous feat few have accomplished.

Due North

Waters contacted his close friend and polar adventurer Eric Larsen to begin planning the journey.

“He said, ‘Let’s go for it,’” Waters says. “Eric had already skied to the North Pole two times, but both times were supported with resupplies being dropped in by airplanes. My big thing was I wanted to do it unsupported, so I could have that clean record doing both poles unsupported.”

It took more than a year and a half of extensive planning, training and securing funding via sponsorships to see the trip come to fruition. A deal was struck with the television network Animal Planet to become a sponsor and film the expedition for a documentary to be aired in the first quarter of 2015.

On day one, the two set out alone from Cape Discovery on Canada’s Ellesmere Island into the vast expanse of unknown water and ice.

“It is by far the most difficult thing I have ever done,” Waters says. “It was definitely a life-changing experience. I remember there was a feeling before climbing Everest and after climbing Everest; you have this different feeling about yourself and your life almost. Now I have this North Pole feeling. It’s a traumatic experience because it’s so difficult; you’re so focused on it, and it’s dangerous the whole time. It was definitely a long process to come away from that trip.”

The pair reached the North Pole after 53 days of skiing, swimming and walking 480 nautical miles through treacherous, polar bear-dodging, sub-zero conditions at best.

“The unsupported expedition to the North Pole is easily one of the most difficult expeditions on the planet,” Larsen says. “We spent 53 days pulling 325-pound sleds day in and day out and almost got eaten by a couple of polar bears. As physically hard as the expedition was, the emotional toll was even greater.”

The two tended to balance each other well throughout the many ups and downs they faced, leaning on each other when times got tough.

“The big difference is Antarctica and the South Pole is ice on top of land, so there’s a continent,” Waters says. “The Arctic and the North Pole is just an ocean with ice floating on the water, so you’re skiing on top of ice that can be anywhere from 10 feet thick in some places down to a mere half-inch thick in others – or no ice at all.”

With tides, temperature and wind affecting ice conditions, cracks and gaps create pans of ice that can range in size from a tiny room to 3 miles across. Depending on the size of the pans, decisions have to be made on whether to ski around them or jump in the freezing water and swim across with a sled in tow.

“The pans may be so long it’s not realistic to try to ski around them because you’re wasting so much time and you need to just keep going,” Waters says. “The mental part is just as hard as the physical because you have so much time to think about things. I remember there were several days where I was thinking about Ole Miss just to keep my mind busy and planning what I’m going to do with my parents and friends the next time I go to a football game weekend in Oxford. It was a great, positive thing that really helped me.”

Whiteouts, polar bears, fatigue and a set timeline to get to the North Pole are just a few of the many life-threatening factors that set the pace for the expedition.

“I like to tell people that I didn’t know we were going to make it even when we were half an hour away from the North Pole,” Waters says. “There are so many variables and uncertainty. It was minus 50 degrees when we started, and it’s constantly evolving. You don’t really ever relax.”

Race to the Finish

As the rendezvous date for the airplane to pick them up grew nearer and the gap to their final destination was not closing in fast enough, the two had to regroup and take a more extreme approach during the final 60-nautical-mile, four-day stretch.

“We started skiing much more in a day than we had been,” Waters says. “We would only sleep for six hours and then be skiing again. It’s 24 hours of sunlight at that point, so we didn’t care if it was night or day anymore. I can remember one day the weather was really bad, and we were just skiing and falling over. We couldn’t navigate or see where we were to make good decisions. I was really down, and Eric and I both started to cry in our goggles. We really had to bond together then and say we can do it, let’s just keep going.”

Only the third and fourth Americans ever to ski unsupported to the North Pole, the two finished the trek in record-breaking time, surpassing the previous American speed record of 55 days by two days.

“Reaching the North Pole in and of itself is a tremendously difficult accomplishment,” Sandok says. “I’m close with Eric and Ryan both, so I was paying a lot of attention and reading their blog posts. In a way, it’s almost like the rest of what he’s done combined times 10. It is really just a tremendous achievement.”

It took nearly two months of recovery for Waters to begin feeling like himself again and for his body to adjust back to normal day-to-day life.

“Eric and I didn’t talk about it that much,” Waters says. “It’s a very humbling place. I’m glad we did it, but I’m also glad it’s over.”

Since returning to Colorado, Waters, an avid outdoor photographer, continues guiding expeditions, and is engaging in public speaking and authoring a book about his trip to Antarctica.

While he looks forward to new expeditions through his guide company, Waters is equally excited to achieve more of his own goals.

“A goal of mine has always been to climb an unclimbed mountain in the Himalayas, and I think that’s going to happen in the next two years,” he says. “Nepal just opened 106 new peaks that were previously closed, and I want to be the first person to climb one. That would be a cool thing.”

By Annie Rhoades

This story was reprinted with permission from the Ole Miss Alumni Review. The Alumni Review is published quarterly for members of the Ole Miss Alumni Association. Join or renew your membership with the Alumni Association today, and don’t miss a single issue.

For questions, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…

Recent Comments