Stacy Bare’s road to Ole Miss was paved with a mix of chance, fate and the intangible lure of a special place. It parallels his later journey into military service, through the throes of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and to ultimate redemption.

Growing up in South Dakota, Bare (BA 00) says he always knew he wanted to be in the U.S. Navy. But in the mid-’90s, as he neared high school graduation, he learned that wasn’t to be.

“I applied for all the different ROTC scholarships, but I was too tall for the Navy,” he says. “I would have had to file medical waivers to get in. The Army gave me a week to decide whether to take [its] scholarship.”

How Bare, now a former U.S. Army captain and Bronze Star recipient, landed at Ole Miss is a familiar tale, not unlike the “how I got to Ole Miss” stories of many out-of-state students with no prior connection to Mississippi.

“I was on my way to the University of Kansas and had more or less pledged a fraternity down there,” Bare explains. “At the time, the Army sent out packets with all the schools that had Army ROTC, and most universities threw in additional scholarship packets, saying that if you get an Army ROTC scholarship, they’d give you an additional scholarship. Since I accepted my scholarship late, I got my packet late. My buddy and I were cruising down this list, and we were calling schools up and kind of having a laugh. We were [both] 17 years old.”

Had it not been for Bulldog staff neglecting its work, Bare might have (gulp) ended up in “the town that fun forgot.”

“This was in March, and Mississippi State was in the Final Four that year,” Bare recalls. He and his friend called State and were sent straight to an answering machine greeting, which told them, “We’re not here today. We’re all watching the Final Four.”

But right below State on the list, Bare saw what they thought was “Olé Miss” — as in the Spanish “olé.”

“We couldn’t believe there was a college called Olé Miss, so we just called ’em. The woman on the phone was so nice and put me through to Maj. Barbour. He ended up flying my dad and me down to take a look at the campus. When you visit Ole Miss, you can’t help but fall in love.”

Bare enrolled, majoring in philosophy (“Dad hung up the phone when I told him,” he recalls), and after a little initial culture shock (during rush, someone told him at least he was from “the right Dakota — South Dakota.”), he settled right in.

“Stacy was one of the brightest students I ever had,” remembers Bill Buppert, an Army captain at the time, later a major and now retired. Buppert taught military science, military history and national security studies. “He was constantly pushing the envelope and never stopped asking questions. We would talk often long after class was over. We learned plenty from each other. There is no doubt that while life has knocked him around a bit, he will prevail.”

Into the Fight

After graduating in 2000, Bare went to Arizona for officer training before being stationed in Germany.

“War broke out in 2001, and I tried to get deployed, and I just couldn’t,” says Bare, still with frustration in his voice. “Eventually I was sent to Sarajevo in 2003 for six months. I felt bad about it. I was getting combat pay for going snowboarding on the weekends, and my parents came for Christmas. Bosnia was relatively stable at the time.”

He later returned to Germany and, upon leaving the military in 2004, moved to Angola with the HALO Trust, the world’s largest humanitarian landmine clearance organization — which then moved him to the former Soviet state of Georgia. But while in Angola, Bare had the chance to go surfing for about three weeks. The experience would prove rejuvenating for him mentally as he connected with nature.

Near the end of 2005, Bare was recalled on reserve to Baghdad, where he relocated to dilapidated, formerly condemned World War II-era barracks. In Baghdad, Bare spent six months on staff and another six months leading a special ops team on patrols and in combat.

“When I look back on my journals from Baghdad, the six months I spent on staff are full of vitriol and frustration,” he says, “and I didn’t really journal that much when I was running around the streets of Baghdad. I was really happy doing that. I enjoyed my time as a team leader, running patrols. Then when I came back, it was reversed. Nightmares came from that time when I was on the street.”

In August 2007, Bare began work on a master’s degree in city planning at the University of Pennsylvania, envisioning he would work around the world rebuilding disaster areas.

“During that time, I began to struggle,” Bare admits. “Before that, I’d gone surfing in South Africa and had grown up spending time in the outdoors, and that gave me some head space, but at Penn, I allowed myself to do drugs and use alcohol, dealing with post-traumatic stress. I had a breakdown.”

After graduating in 2009, Bare took a job in Colorado with Veterans Green Jobs, an organization that aims to help transition vets back into civilian life with “meaningful employment opportunities that serve our communities and environment.”

Bare’s story could have met a grim end then. He says the job was great, but PTSD hounded him like a black dog. He thought about suicide, and it was a real prospect. In fact, a report from the Center for a New American Security calculates that from 2005 to 2010, service members committed suicide at a rate of about one every 36 hours. The Army reported a record number of suicides in July 2011, when 33 active and reserve component service members took their own lives, the report states.

Mountains to Climb

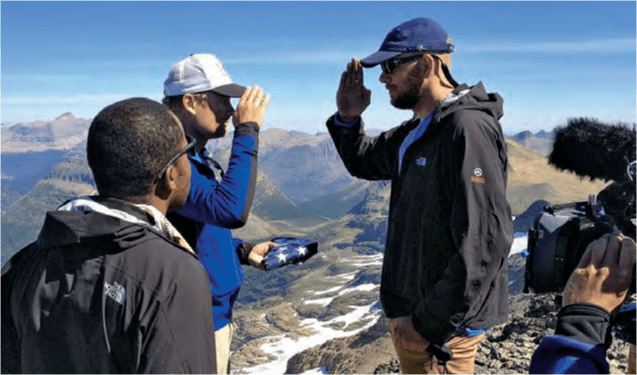

While Bare’s thoughts and emotions whirled, a friend invited him to go rock climbing. Soon he was rock climbing often, which provided him the same restorative, calming effect nature had on him during his stint surfing in Angola. It inspired him to seek and obtain a grant from Force Factor to fund his idea to take other recent veterans outdoors. Bare’s idea was put into action by founding Veterans Expeditions with former Army ranger Nick Watson in 2010.

Before long, Bare left the group to put his experience to work as a national representative for the Military Families and Veterans Initiative on the Sierra Club Mission Outdoors team, guiding veterans into nature to help them enjoy its benefits. In July 2012, he was promoted to team director, overseeing 7,000 volunteer leaders and helping 250,000 Americans get outside each year — with only a staff of five managing the program.

“We’re trying to inspire all of America to get out and appreciate just how amazing this country is,” Bare says. “When you’re outside, there are a few key things that happen. Even in the sense of the Grove — people hanging out outside in a beautiful environment. Things fade away, especially if you get out a little farther. Your social class, economic background and race, those things don’t really matter anymore. You’re all out there doing the same thing: paddling or hiking or whatever.

“We’re inundated with information. We’re always on our phones. The outdoors is what attracted our ancestors to America in the first place. All of a sudden, it becomes clear to you and clicks an idea in your mind that you can’t work out back home. When you’ve been outside and go back home, you’re a happier person.”

Rock climbing in particular, Bare says, requires such focus “on the problem in front of you, that your mind is focused. You get clarity that you’re not able to in town. Things like trauma stay away, and you begin to retrain your mind. Slowly but surely, those things begin to transfer over to your in-town life.”

Bare changed the notion of the initiative, says Melanie Mac Innis, assistant director for volunteer engagement for Sierra Club’s Mission Outdoors.

“It went from being an initiative that found participants to send on outdoor adventures with non-Sierra Club programs to a movement to get the military/vet population connected to the outdoors, to the Sierra Club and to themselves. He took a risk, and it’s beginning to stick.”

Though Bare attributes his salvation to the outdoors, he also credits the people in his life who helped him through the dark, sometimes suicidal path that got him there.

“The commitment that a lot of Mississippians have to supporting our troops is really legitimate,” Bare posits. “It’s not just a magnet on a car. My friends from Ole Miss really took care of me when I was gone and when I was back home. A lot of what I’ve accomplished has been through the support of guys and gals I met at Ole Miss. But even with all that support, I still struggled, and it was a significant journey to get where I am today. I can only imagine what it’s like for people who don’t have that type of support.”

By Tad Wilkes (BA 94, JD 00), an attorney and writer living in Oxford.

This story was reprinted with permission from the Ole Miss Alumni Review. The Alumni Review is published quarterly for members of the Ole Miss Alumni Association. Join or renew your membership with the Alumni Association today, and don’t miss a single issue.

For questions, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Recent Comments