Who built the mounds? Why did they leave? Where did they go? Archaeologists are still digging for answers.

This story was republished by permission of the Meek School of Journalism and New Media.

WINTERVILLE — Amid vast fields of corn, cotton and soy in the flat expanse of the Mississippi Delta, 12 unnatural masses of land stand like grassy trapezoids risen out of the dirt. Eight hundred years ago, at this site one mile south of Greenville, Native American hands built something special.

This place, home to one of the tallest mounds between the Emerald Mound in Natchez and Cahokia in Illinois, is shrouded in an air of mystery. Archaeologists still theorize on exactly who built the mounds and what led to their disappearance.

The Winterville Mounds are now considered an important piece of the puzzle of pre-historic Mississippi natives. They are home to heaps of historical information, artifacts, and human bones — all clues to what happened here.

In 1907, archaeologist C.B. Moore ventured from his usual excavation site in Moundville, Ala., and sank over 100 holes at Winterville. He didn’t find anything he considered worthy of further exploration, such as pottery or human remains.

Luckily, when word got out that he had found nothing, people left the mounds virtually untouched and, most importantly, un-looted.

It wasn’t until Jeffrey Brain’s extensive investigation of the site in partnership with the Lower Mississippi Survey at Harvard University in 1967 that it was revealed to be an important piece of Native American history. Brain’s photo now hangs in a place of honor at the small state museum here.

In 1939, as farms and highway construction threatened the mounds, the Greenville Garden Club bought the property to preserve it. About 40 years later, it became a state park, and in 1993, a National Historic Landmark. Now, schools in the area use it for educational field trips.

In the mornings, site director Mark Howell and archaeologist Mark Dingeldein host groups of youth, who explore the mounds, participate in interactive activities, and examine artifacts from Winterville and the surrounding Delta.

Ultimately, the site will be home to a larger museum and even more interactive educational opportunities. In 2015, the Legislature passed a bond bill that gave Winterville $300,000 to restore the site.

There are plans for a new gate and totem poles representing eight Mississippi tribes surrounding the museum. The new museum will encapsulate all of Mississippi’s Native American history — not just that of the Winterville site.

“The [museum] we have was built in ’68… It’s got problems. It’s not really large enough to suit our purposes, particularly since this is the biggest site in Mississippi,” Howell said.

Indeed, Winterville is a special jewel on the state’s new Mound Trail, which invites tourists and residents to explore the many mounds built by some of the 22 tribes that populated Mississippi more than 200 years ago.

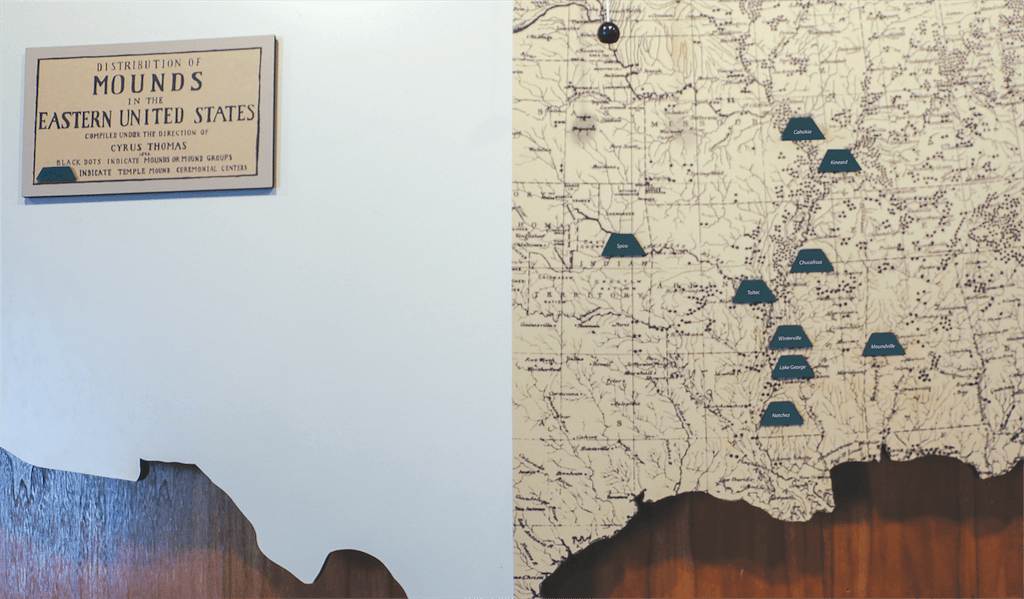

The bunker-like museum, which from the outside looks like a small, grassy mound, is home to various artifacts, maps and explanatory posters. Within the mounds, layers of long-buried history wait to be extracted from the packed dirt.

Some of what has already been unearthed: bones from burial mounds, pottery both intact and in shards, tools, and arrowheads, or “projectile points.” Some are made from rock, such as obsidian or quartz, that had to have traveled a great distance to find a resting place in Mississippi. This indicates that the Winterville site was a stopping-off point on Native American trade routes.

“You have rock that comes from as far east as North Georgia and also from Arkansas and Oklahoma. A lot of it was all pretty much from the Delta, but where are you going to get this black obsidian in the Mississippi Delta? You’re not. Quartz? No. You’re going to have to go up in the mountains somewhere,” Dingeldein said.

People did not often occupy the site itself, but rather, surrounding villages. Dingledein describes the area as a ceremonial site or center for trading, operating much like a fair of sorts.

The mysterious builders have left hints in layers of the mounds, such as the remains of burned homes or ceremonial structures. Digs have indicated that a large complex succumbed to a spectacular fire in the biggest mound. These types of findings have given rise to all sorts of speculation as to what went on here.

Howell said radiocarbon dating shows Winterville was most likely abandoned in the 1600s, before the first French explorers appeared.

“The first documentation of people here, written documentation, is by (Spanish conquistador Hernando) de Soto. There’s some pretty good documentation of frontal nations, cities, people in the Mississippi Delta and across the river into Arkansas,” Howell said.

By “de Soto,” Howell is referring to the chroniclers of his expedition in 1540, which left archaeologists with a slew of information about Mississippi natives. Historians caution that some of these accounts are inevitably polluted with inaccuracies because of the language barrier between the Spanish and the natives.

Nonetheless, they write of place names and chiefdoms, which can help pinpoint language groups, Howell said. In 1542, de Soto died and, according to legend, his body was tossed into the Mississippi River to keep news of his death from the natives.

A puzzle piece in the ongoing mystery of Winterville’s history is an ancient city known as Quigualcum. Spanish chroniclers wrote of the city. Though it was most likely misspelled due to the language barrier, Howell said archaeologists theorize that Winterville could be this ancient city.

“Because of geography and now because of radiocarbon dating, because of the size of Winterville and where the Spanish were when they came across this name, there are some theories. It’s being renewed now, that Winterville, its real name was Quigualcum. If that’s true, this puts a real name to a place — a really neat name to a place — and also puts it in history,” he said.

The etymology of the word leads historians to believe that the people who settled near Winterville spoke an early Tunican language.

What they do know is that these people were not part of any known tribe today, but that whoever was left of these people eventually did disperse and become part of what would become Choctaw, Tunica, and other Native American tribes.

Many of the people at Winterville disappeared because of European disease and violence, but where the remainder went is unknown. According to Howell, in spite of the fertile nature of the Delta, people never returned to the site once they left.

Perhaps clues lie in the many layers of dirt on Winterville’s 42 acres. Perhaps historians will never know exactly what civilization held what kind of ceremonies or traded at the site in 1,000 A.D., and then abandoned it. A slew of researchers, including Howell and Dingeldein, are painstakingly putting pieces together, trying to paint a picture of what once was.

But not all research on the site is purely dig-in-the-dirt archeological.

An archaeoastronomer, William Romain, looked at the site from a cosmic perspective and discovered that key mounds line up perfectly with the moon when it reaches a major lunar standstill. (Lunar standstills occur every 18.6 years, when the range of the declination of the moon reaches a maximum. As a result, at high latitudes, the moon’s greatest altitude changes in just two weeks from high in the sky to low over the horizon.) The three largest mounds sit in line, marching directly toward the moon every 18 or so years, when it dips down to its southernmost point.

Was this harmony between the mounds and the moon planned? Why? And what does it mean?

Like so many puzzles at Winterville, it remains a mystery.

By Zoe McDonald. Photography by Chi Kalu.

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…

Recent Comments