Leslie M. Westbrook knows how big ideas become even bigger brands. Not only that, the University of Mississippi alumna is teaching Meek School students how innovative branding and consumer research can help products to expand markets, pull ahead of the competition and stay there.

An acclaimed Fortune 500 consumer research specialist, Westbrook’s career started in the market research department with Procter & Gamble in 1968 and eventually led to the establishment of her own firm, Leslie M. Westbrook & Associates in Easton, Maryland. The Chesapeake Bay-area resident has been a key force in the development of worldwide brands. A short list includes Pampers, Pringles, Head & Shoulders, Dunkin’ Donuts Coffee, the Dairy Queen Blizzard and many more.

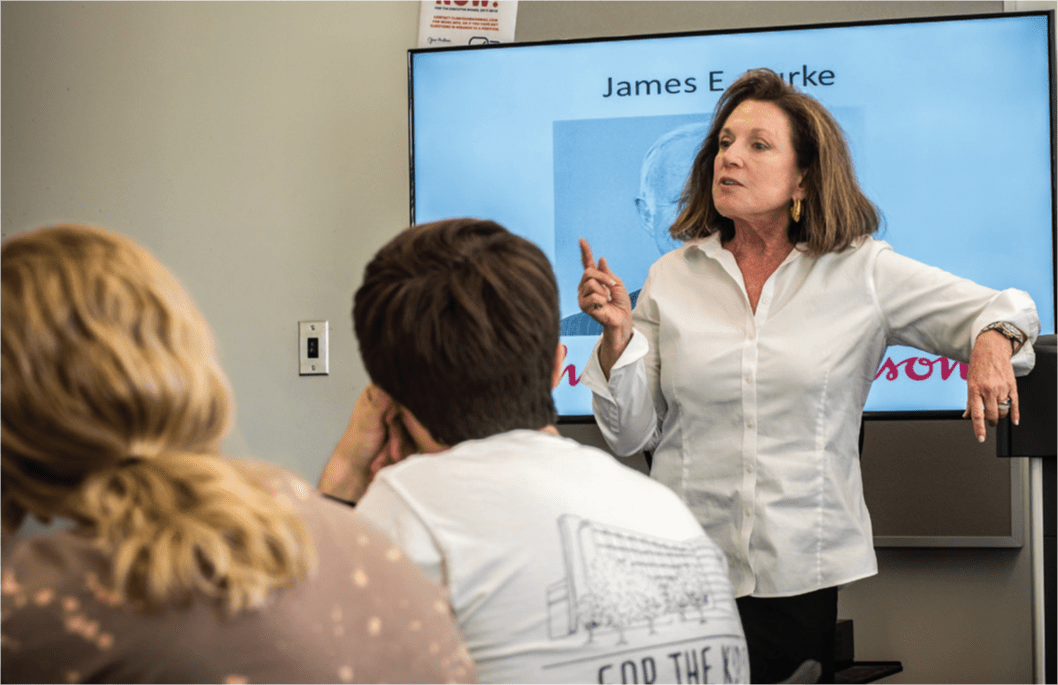

Once a year, Meek School undergraduates who study integrated marketing communications have the chance to learn first-hand from Westbrook as part of a global brands course of her own design that is taught during May intersession. The course examines international brands that maintain their leadership role in consumer markets and those that do not.

As a teacher, Westbrook draws on her own market research development experiences to provide insight to students. Behind each brand the students study is a story of innovation — How, for instance, did Pringles get introduced to American consumers?

Just ask her. She was there.

“One of my core competencies is language and wordsmithing,” Westbrook said. “Pringles is a good example of that. They weren’t like Lay’s potato chips because they were made from a potato mixture. But (the client) wanted to call them ‘chips’ because they didn’t want to label them as ‘potato forms’ or ‘potato snacks.’ So, Pringles became known as the ‘newfangled potato chips.’ Lay’s eventually brought lawsuits over this, but by that time, the Pringles brand was established. Pringles were Pringles. It was a revolutionary product because it was something that was completely new to the market.”

However, teaching is just the first of many ways, Westbrook is helping shape the future of Meek School. Last fall, Westbrook pledged a $500,000 gift to UM to endow a state-of-the-art consumer research center that will prepare future students to be fluent in a variety of research methods including in-depth interviews, surveys, focus groups and more.

Westbrook will play a key role in the design of the facility. With the right setup, the Meek School could not only help students learn with extensive hands-on experience, but also interact with external clients and offer market research consultation services, she said.

“The first thing we need is an authentic focus group facility,” Westbrook explained. “A focus group facility will have two rooms adjoined with a one-way mirror. We could do so much with students in a facility like that.”

Westbrook’s professional journey started at Ole Miss, where she was an education major and was voted Miss Ole Miss in 1968. By senior year, her life appeared to be on a set path. The Jackson native was engaged to her college sweetheart and planning on starting her career as an English teacher.

However, Westbook canceled what she likes to refer to as her “big, fat, Southern wedding” and set down a new path that eventually led her to become one of the nation’s top consumer researchers.

Through a sorority sister from Ole Miss, Westbrook was offered the chance to train as a market research specialist with Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati. She jumped at the chance.

In those days, the life of a young professional working in market research for Procter & Gamble was something like being a secret agent. Many of the products in development required “technical insulation,” meaning they were top secret in order to beat out competitors and ensure first-mover advantage in the market.

Procter & Gamble took such caution to conceal the identity of their research specialists at that time that Westbrook and her colleagues all carried business cards bearing the company name Grandin Market Research, which was officially a separate business on the other side of the Ohio River, technically in Kentucky.

In those days, Westbrook lived from hotel to hotel and didn’t know where her next assignment from Grandin Market Research (really Procter & Gamble) would send her.

– Leslie M. Westbrook

“For three years, I lived out of five suitcases and I didn’t have a home,” remembers Westbrook. “Every Thursday was telegram day. It would tell us where we were going and who we were meeting, but not who the client was because that, of course, was a secret. Procter & Gamble bought an apartment building and when they would send us back to Cincinnati, we would all stay there. Being right out of college and being paid to travel all around the country was very exciting.”

In the 1960s, being a woman in market research was a ground-breaking role that helped set the stage for future women to be market researchers, as well. Perhaps this is best seen in her contribution to the development of Pampers disposable diapers.

“In the 1960s, consumer researchers were all men,” Westbrook said. “They thought that (Pampers) marketing was going to be based on convenience. But, when I spoke with mothers, the diapering process was described as a labor of love and convenience wasn’t important to them. They said that worrying about convenience would make them feel like bad mothers. That’s how Pampers became called ‘Pampers.’ Mothers want to pamper their babies.”

Perhaps the highest-profile case of Westbrook’s career came during the 1982 Tylenol poisoning crisis, a crisis management case study that is taught in business and communication schools across the globe.

In September and October of that year, seven people from the Chicago area suddenly died, with all autopsies linking to tampered capsules of Tylenol containing potassium cyanide. Owned by McNeil Consumer Products, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, the medication held 35 percent of U.S. market share in over-the-counter pain relievers before the crisis — that number quickly fell to less than 8 percent.

However, with leadership from Johnson & Johnson CEO James Burke, the corporation made a series of moves that, while costly at the time, retained consumer confidence in the brand, and shaped the way people consume medicine worldwide to this day. More than 31 million bottles of Tylenol capsules were recalled from store shelves at a cost of more than $100 million. The corporation ran ads nationwide asking people to trade in their capsules for tablets. Factories stopped manufacturing capsules. They were out of the capsule business.

Tylenol had to fix its product, which is where Westbrook came in.

“What I worked on was finding out what people were willing to try,” Westbrook said. “We had to balance what people loved about the capsule with their fear of taking it.”

Already the owner of her own firm, she was brought in three months after the poisonings to lead the consumer research efforts to overhaul Tylenol’s product. Through a series of focus groups in the Chicago area and back-and-forth work between Tylenol’s research and development team, she helped create and field test the Tylenol “caplet,” a hybrid that offered the safety of a tablet and the easy-to-swallow coating that made Tylenol’s two-toned capsules so popular. She also helped field test and wordsmith Tylenol’s safety-sealed, tamper-resistant packaging.

“It’s hard to imagine a world where medications didn’t have safety seals, but before that, they never had them,” she explained. “We tested both the seal of the bottle and then the outer package of the box and we were testing different language for the new safety packaging. Our lawyers said we couldn’t say ‘tamper-proof’ and so we came up with ‘triple-sealed, tamper-resistant’ packaging. That’s what brought people back to Tylenol, the safety packaging.”

Tylenol’s work paved the way for the manner in which all food and medicine are consumed today. Following the launch of Tylenol’s caplet, Congress passed a bill in 1983 that made it a federal offense to tamper with consumer goods. In 1989, the FDA established a regulation that required all manufacturers of consumer goods to make their own products tamper-resistant.

Today, Westbrook lives on the Chesapeake Bay with her husband Paolo Frigerio. When she’s not working with Meek School students, she spends her time doing pro bono work and pursuing other passions including painting.

As for aspiring market researchers of tomorrow, Westbrook encourages students to jump at every opportunity for experience they can, and most importantly, make connections.

“Do informational interviews,” she said. “I don’t know anyone in the workforce who isn’t willing to give you 15 or 20 minutes. You will learn so much and that will help guide you. Everything you do on every job you take on adds up to a bigger picture. You may not know what that bigger picture is today. But, you will.”

By Andrew M. Abernathy. Photography by Timothy Ivy.

The Meek School Magazine is a collaborative effort of Journalism and Integrated Marketing Communications students with the faculty of Meek School of Journalism and New Media. Every week, for the next few weeks, HottyToddy.com will feature an article from Meek Magazine, Issue 5 (2017-2018).

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Recent Comments