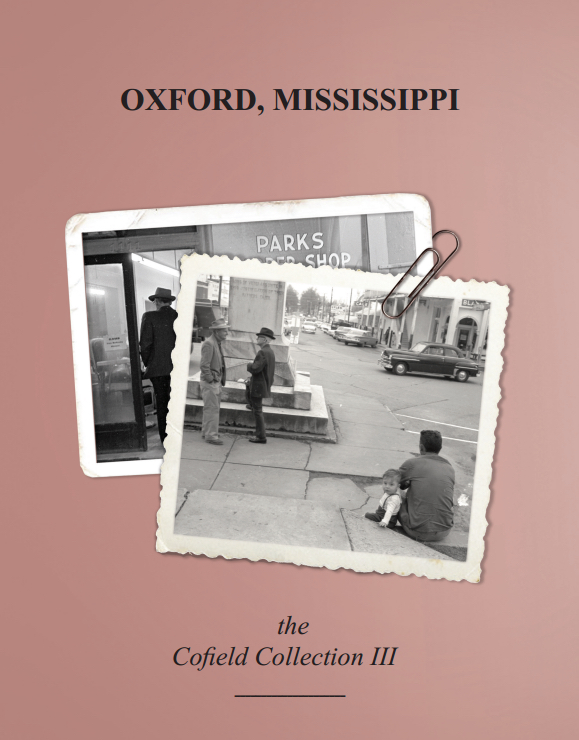

Editor’s Note: John Cofield will hold a book signing for “Oxford, Mississippi: The Cofield

Collection, Volume Three” at 5:30 p.m. Wednesday, November 8, 2023, at Off-Square Books.

“We are Southern Americana at its finest,” John Cofield claimed in his first book, “as colorful a population of Southern ladies and gentlemen, leaders and characters, both famous and infamous, as any Southern setting anywhere.”

That was a notable boast, but one that now – the better part of a decade later – Cofield has consistently managed to make good.

John Cofield is Oxford’s most notable local historian. He is a worthy successor to his father, Jack Cofield, and grandfather, J.R. “Colonel” Cofield (who opened his Oxford photography shop in 1928).

Just as Faulkner found he could write forever about “my own little postage stamp of native soil,” Cofield concludes, “I, too, learned along the way that my hometown had all the photographs I could ever write about, and that I would never live long enough to exhaust it.”

Cofield also acknowledges the temptations and rewards of modern technology.

“Within minutes of becoming a Facebooker, I realized people really liked the old black-and-whites of the town and county, and there I was with boxes, drawers, and cedar chests full of old photographs. . . . Soon the game changed when town friends began sending me their old family photos saying, ‘They’ll get more coverage on your page than anywhere else.’”

Volume I of “The Cofield Collection” (2017) started on North Lamar and ran to the Square. Volume II (2022) mapped the east side of Oxford. It ran from Avent Park to the Kream Kup – dwelt on the “the Velvet Ditch,” the dip behind the east side of the Square, home to cotton gins and bars and the Hoka – and looked west down Jackson Avenue toward the railroad depot. This volume is broader, stretching out as far as Abbeville and Taylor and WSUH.

The chapter “Squatters’ Rights” recalls those nights in the 70s when the Square was deserted after dusk. (“Cofield, I dare you to walk down the middle of the street and stand under the red light and smoke a cigarette, and walk back up here.”)

From modern times, there are recollections of more restaurants than you can readily count — a whole photo montage page. Ironically, this is foreshadowed with black-and-white photos of Seay’s Mansion House. Cofield notes that Percy Sledge ate at Seay’s before a fraternity dance, the first black person to be served there (in 1966, the same year he recorded “When A Man Loves A Woman”).

“The Road to the Lyceum” meanders en route through Bailey’s Woods, and, with a stopover at the depot, takes in W.C. Handy’s “Ole Miss Rag.” Clifton Bondurant Webb remembers Handy playing at an Ole Miss dance, with young Bill Faulkner leading the grand march. Handy’s music figures in the Snopes trilogy, as it provides the title of “That Evening Sun.” Those connections would be made later, after the years in which Faulkner posed for a group photo with his SAE brother.

With shots of Shine Morgan’s truck unloading refrigerators from a boxcar, the book bounces back to the Morgan appliance store on the Square – then south along the rail line to Thacker Mountain and north to the Tallahatchie River bridge. There was passenger traffic, too, students and others.

Oxford historian Susie Marshall recalls hoboes begging food at the back door of her mother’s boardinghouse, and black working men flooding into town to help build dormitories. Cofield notes that the University of Mississippi campus has been rated among the nation’s most beautiful.

When looking at the Lyceum, he observes, “If you can’t feel it, you aren’t a Rebel.”

Yet he has looked straight-faced at what Faulkner came finally to acknowledge, what is as clear

“as the wealthy white men who built the Lyceum and as black as the slaves who made every

brick.”

“Any attempt to add a coating of outsider sugar serves only to hide the raw truth that Ole Miss

has been a tightly woven two-stranded rope, of opposite colors, from the intellectual moment

of her birth…

“Our only responsibility as stewards is to insure Ole Miss’s history is preserved and intact for

the future. But more than anything else, it has to be the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

. . . The view back over our Rebel shoulders is a clear shot of our black and white heritage.”

The Dead House that held the casualties of Shiloh became the Delta Kappa Epsilon chapter house. The Confederate memorial looking east from the Circle rhymes with the statue of James Meredith walking east toward the Lyceum.

This is a book you will appreciate if you camped out with David Kellum, long before he was the Voice of the Rebels; if you remember the yeast rolls served in Oxford schools; if you glimpsed Lauren Hutton visiting her family; if you will prize two cake recipes from Ms. George Isaiah’s Busy Bee Café.

As well as his own family’s collections, Cofield draws on the images of Martin Dain, Ed Meek, and families from Oxford. He freely acknowledges the aid of Deborah Freeland, whose experience as an artist, photographer, and graphic designer has shaped these books and put them in final form. Her aerial view of the campus in 1861 shows a wizardry compounded of all these talents.

This book is not governed by strict geography or chronology. As with “Ulysses” and “Catch-22,” it runs along lines of association and memory.

OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI: The Cofield Collection, Volume III, by John Cofield. Cofield Press,

http://cofieldpress.com/ . 328 pages. $49.95.

Allen Boyer, book editor of HottyToddy, grew up in Oxford and on the Ole Miss campus.

Recent Comments