Editor’s Note: Grace Elizabeth Hale will hold a book signing for “Into the Pines” at 5:30 p.m. Tuesday, November 14, 2023, at Off-Square Books. Hale will be in conversation with friend and

author Ralph Eubanks.

As Grace Elizabeth Hale heard the story, her grandfather had been a hero, “just like Gregory Peck playing Atticus Finch.”

As the sheriff of Jefferson Davis County, deep in the Piney Woods, he had faced down a lynch mob. He had arrested a black man charged with rape.

“No one is taking a man out of my jail,” he had told the mob, and they had dispersed. Then, the next morning, her grandfather had gone home to get some sleep.

“In his absence, his deputies and a highway patrolman took the alleged rapist to the scene of the crime . . . . There, the Black man attempted to escape, grabbing the patrolman’s improperly holstered gun. The officers had no alternative but to shoot. My grandfather was upset at the patrolman’s negligence, according to my mother. But he also believed that the accused man had chosen to die this way rather than be lynched or executed in Mississippi’s mobile electric chair.”

Hale teaches history at the University of Virginia. Reared in Georgia – having spent happy childhood vacations at her grandparents’ home in Prentiss, the county seat of Jefferson Davis County – Hale came finally to look up details of how Versie Johnson had met his death in 1947.

What she saw in the yellowing pages of the Prentiss Headlight, and learned in talking with members of the community – most notably, an elderly black man who had known the black undertaker who buried Johnson’s body – came to trouble her deeply. “In the Pines” is the story of the search she undertook.

The news stories did not limit the story to a troubled night and a tragic day. They described events that might have unfolded over a week. There may have been no police report of a lynching; black people in Prentiss spoke of an interracial love affair. It may not have been a cowardly mob that dispersed; it may have been a mob that gave the sheriff until nightfall to do something.

Most disturbing, her grandfather had not been at home asleep. The newspapers said he had been at the scene, in charge, when his prisoner was shot.

Hale turned to her family for answers, and found none. “My grandmother said she did not remember anything about Johnson’s killing. Even then, I understood that her answer was a lie.”

Hale reconstructs the landscape in which Versie Johnson died. Traveling homeward from Jackson, and its airport named for Medgar Evers, she notes the ravages wrought by the lumber business on the pine forests. The railroads came and brought the lumber tracks and sawmills.

In 1906, Jefferson Davis County was carved out of neighboring counties; in Prentiss, half the blocks were deeded to the railroad. The black section of town was called the Sawmill Quarters. In Jeff Davis County, white people prided themselves on good race relations, often meaning that there had been only one lynching. Surprisingly, black people did surprisingly well.

A New Deal survey of the county counted 900 black families farming as tenants or sharecroppers, but 600 owning their own land, “an astonishingly high rate of property ownership for Black southerners.”

Many black citizens even voted, until a purge of the voter rolls in 1956 – part of the South’s resistance to integration – cut the number of black voters from 1,200 to 100. The Prentiss Institute, a black school modeled on the Tuskegee Institute, offered classes that took students beyond what one-room black schoolhouses offered.

“People from elsewhere tend to think of Mississippi as somehow outside of time, stuck in the past and isolated.” She rejects this: “In the Piney Woods, radical change has shaped the lives of people in every generation…. Since the early nineteenth century, there has never been enough peace in this place to establish something as static as ‘a way of life.’”

Racial tensions were quiet but eternal. Lynchings were uncommon in Jeff Davis County, but infamous elsewhere in the Piney Woods. Jeff Davis County voted dry but many bootleggers were black. The Second World War broadened black Americans’ horizons, with military service and defense work jobs; the Prentiss Headlight warned black readers that “white supremacy has always prevailed and always will.”

Versie Johnson’s poverty and the ubiquity of his surname make it difficult to trace him. Census and draft records supply locations but few details. He may have been a runner for a bootlegger. The rumor and circumlocution surrounding his death (the crowd outside the jail was dubiously called “large but orderly”) obscure the facts. Newspapers supplied differing details.

If the facts of the individual case remain murky, the overall pattern is clear. “On some level, my grandfather and the other white men and women who led Jeff Davis in those years must have known that what they were doing was shortsighted and wrong,” Hale pointedly concludes.

Versie Johnson’s death “made it clear just how far white residents were willing to go to preserve white supremacy.”

Hale’s grandfather died when she was fifteen. The Prentiss Institute has closed, having made its way for eighty years as a community school, a high school, a normal school and industrial institute, a Bible college, and a junior college. Neither white supremacy nor black resilience brought lasting prosperity.

The county has faded with the loss of jobs and local light industry.

A black public school and a white Christian academy both struggle.

John Grisham, whose book “The Reckoning” ranks as a quietly eloquent historical novel about Mississippi in the 1940s, supplies a preface to “In the Pines.” He lists the toll of recorded lynchings: 4,400 total, 659 in Mississippi. His own family, Grisham acknowledges, “were not the ones who joined mobs. They were, however, part of the culture that looked the other way as their friends and neighbors did so.”

“I taught southern history, even as I ran away from my family’s past,” Hale comments.

The history she unearths here is more than the story of an all-but-anonymous black man and the lawman who did not save him.

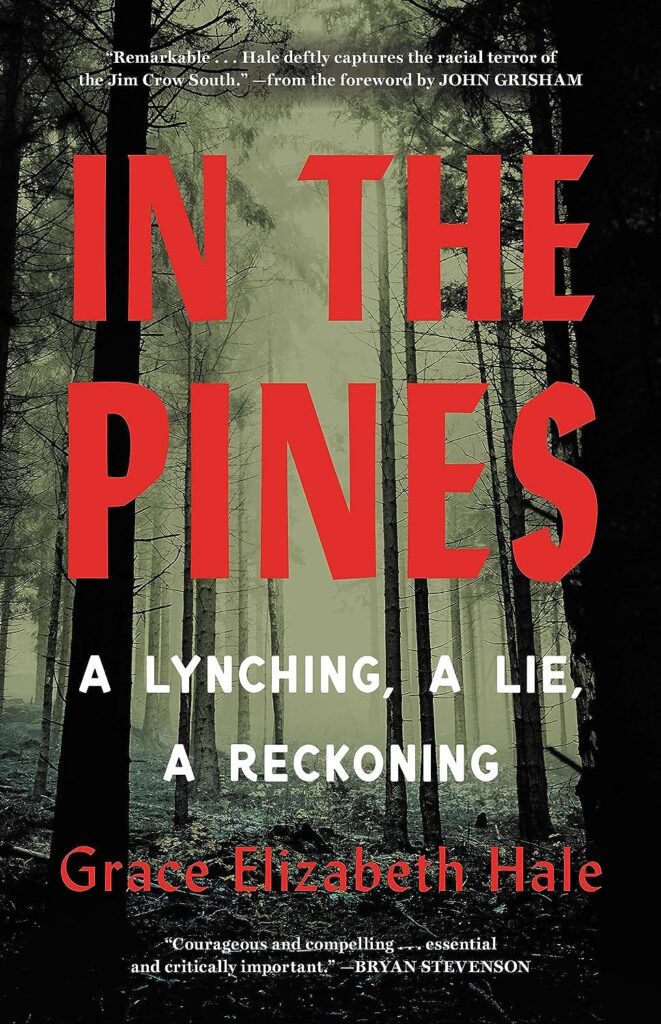

“In the Pines: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning,” by Grace Elizabeth Hale. Little, Brown and

Company. 256 pages. $29.00.

Allen Boyer is the book editor of HottyToddy.com. A native of Oxford, he lives and writes on

Staten Island.

Recent Comments